4.1 The extent to which evaluation is called for

1

In this chapter we provide an evaluation of the firearms licensing system with a particular focus on the firearms licensing process and the regulation of semi-automatic firearms. However, it should be noted that our Terms of Reference restricted us from inquiring into or making recommendations on “amendments to firearms legislation” as “the Government is separately pursuing this issue”.

2

The government’s separate pursuit of this issue has led to significant changes to the regulation of semi-automatic firearms and the prohibition of certain types of ammunition and magazines following the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack. The Arms Legislation Act 2020 introduced further substantial changes to the firearms licensing system. The amendments:

- substantially recast the approach to be taken to the fit and proper person test;

- provide mechanisms for health assessments to play a role in the licensing process;

- reduce the duration of firearms licences from ten to five years for first time applicants and limit the duration of firearms licences to five years for those who have previously had their licence revoked, surrendered or expired;

- provide for ongoing inspection of firearms and storage arrangements; and

- provide explicitly for fees to be fixed on the basis of cost recovery.

3

Our Terms of Reference precluded recommendations on the regulation of semi-automatic firearms and the legislative structure of the firearms licensing process. So it is not open to us to recommend legislative changes affecting the way in which the fit and proper person test is applied. On the other hand, we could make recommendations on the administration of this test by New Zealand Police. Complicating the situation is that any changes we recommend might be addressed by changes in New Zealand Police practice or legislatively, as demonstrated by recent amendments to the Arms Act 1983.

4

The firearms licensing system is required to give effect to the legislative framework in which it operates. For the most part, the issues we have identified with the firearms licensing system (and which we discuss in this chapter) were recognised and understood by New Zealand Police before 15 March 2019 and have been addressed by legislation passed after 15 March 2019.

5

Against this background the practical scope for recommendations is more limited than would otherwise be the case.

6

All of that said, some evaluation of the way in which the firearms licensing system operated prior to 15 March 2019 is necessary because:

- it provides an important part of the explanation for why the individual’s firearms licence application was granted and the context in which those who dealt with that application were acting;

- an understanding of why the firearms licensing process was less than ideal may provide some assistance for the future;

- the ease with which restrictions on military style semi-automatic firearms could be exploited explains why the individual was able to legally acquire the components of the military style semi-automatic rifles he used in the terrorist attack;

- more generally, the fact that known risks and deficiencies in the firearms licensing system were not addressed warrants mention; and

- finally, we consider that, despite the direction in our Terms of Reference, there remains scope for some recommendations.

4.2 Overview of this chapter

7

In the rest of this chapter, we discuss:

- the general operation and scale of the firearms licensing system;

- the overall effectiveness of the firearms licensing system;

- the social and political context in which the firearms licensing system operates;

- resourcing;

- issues with administration;

- the limited guidance given by the Arms Manual, the Master Vetting Guide and the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide;

- the ease of obtaining a firearms licence;

- reviews, reports and commentary on the firearms licensing system; and

- our conclusions on the firearms licensing system.

4.3 The general operation and scale of the firearms licensing system

8

As at 31 October 2018, there were 248,764 current firearms licences, including standard, dealer and visitor licences.

9

Firearms licensing is largely administered by New Zealand Police on a District by District basis, with the exception of certain statutory powers that are exercised within the Arms Act Service Delivery Group in Police National Headquarters. These exceptions are not material for present purposes.

10

Records of legally-owned firearms were kept only for military style semi‑automatic firearms, pistols, and restricted weapons. These were based on permits to import and procure and were not part of a formal registry. There is no record of the total number of firearms in legal ownership in New Zealand and, of course, the number of illegally-owned firearms is unknown. There have been a range of estimates:

- In 1997, the Thorp Report estimated the total number of civilian-owned firearms in New Zealand, including both legal and illegal firearms, to be between 700,000 and 1,000,000. This included an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 military style semi-automatic firearms.14

- In 2014, New Zealand Police estimated the total number of civilian-owned firearms to be around 1.2 million.

- A 2018 report estimated that there were 1.212 million civilian owned firearms – approximately 2.6 firearms for every ten people.15 Of these, 65,837 were military style semi-automatic firearms, pistols and restricted weapons recorded as held by 9,722 licensed owners.16 Around two thirds of the 65,837 were pistols.17

11

There are fewer licences than firearms, as many firearms licence holders own more than one firearm. Although the numbers are only rough estimates, dividing the number of firearms (approximately 1.2 million) by the number of licensees (approximately 250,000) suggests that licence holders, on average, own just under five firearms. This indicates that the number of firearms owned by the individual (six as at 15 March 2019) was not unusual within the firearms community.

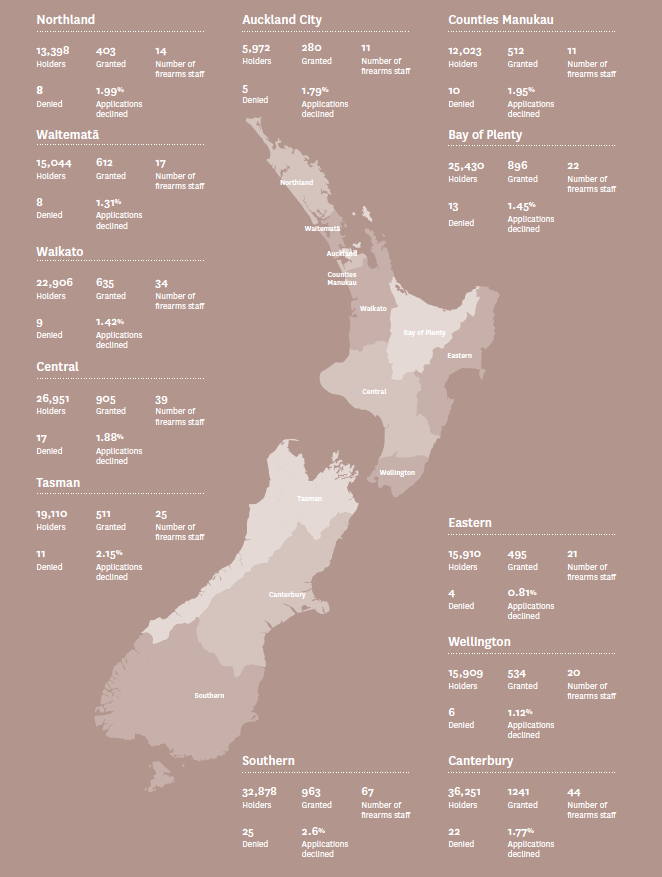

Figure 18: Firearms licences by District, number of firearms staff and new standard firearms licence applications granted and denied in 2017

4.4 The overall effectiveness of the firearms licensing system

12

By international standards, New Zealand’s firearms licensing process is strict due to the requirements for referees, face-to-face interviews with applicants and referees and inspection of firearms storage arrangements. And, on the whole, before 15 March 2019 the licensing system appeared to have been reasonably successful, at least as measured by the limited number of its failures.

13

There were 2,181 hospitalisations due to firearms-related injuries between 2000 and 2017, an average of 121 per year.18 There were 867 firearms deaths from 2000 to 2015, an average of 54 a year. The most common cause of death by firearm was suicide, accounting for around 40 deaths a year. Between 2010 and 2017 there were around seven homicides a year caused by firearms. Behind these statistics are a large number of incidents, all of which were serious and many tragic. That said, these are comparatively low figures, particularly allowing for the number of firearms in circulation, the availability of semi-automatic firearms and easily evadable controls in relation to military style semi-automatic firearms.

4.5 The social and political context in which the firearms licensing system operates

14

Over the last 30 years, firearms licensing and control in New Zealand has been controversial and has involved something of a cultural divide. Deficiencies in the firearms licensing system had been recognised in a number of reports and reviews. Changes to the firearms licensing system tend to involve additional expenses and inconvenience for, or restrictions on, firearms owners and are likely to attract their opposition. Given the number of firearms owners, their concerns are taken seriously by politicians. This, along with the perception that the licensing system was reasonably effective, contributed to a lack of political appetite for reform prior to 15 March 2019.

15

Licensed firearms owners engage closely with New Zealand Police. For some time relationships were difficult, as is apparent from issues (and litigation) involving New Zealand Police’s administration of the rules about military style semi-automatic firearms. There were also issues with the timeliness (or otherwise) of the processing of firearms licence applications. A response was the 2013 establishment of the Firearms Community Advisory Forum. Its purposes were to improve the relationship between the firearms community and New Zealand Police and, in particular, to provide input to New Zealand Police on policy relating to the Arms Act and the Arms Regulations 1992 and review and make recommendations for consideration by New Zealand Police on firearms-related matters.

16

There was a sense that firearms licensing involves the delivery of a service for which licensed firearms owners are the customers. Consistent with this are an emphasis in the Key Performance Indicators for District Arms Officers on ensuring timely processing of applications and the 2017 establishment of the Arms Act Service Delivery Group within New Zealand Police. The two main objectives of the Arms Act Service Delivery Group are to improve the relationship with the firearms community and to improve how New Zealand Police administers the Arms Act. In doing so, the Arms Act Service Delivery Group aims to provide “a more customer-focused and efficient public service”.

4.6 Resourcing

17

The application fee for a standard firearms licence is $123.75 and the licence is valid for ten years. As at 15 March 2019, fees charged for firearms licences had not increased since 1999. The fee is Goods and Services Tax (GST) inclusive. So at the time it was fixed, it represented a fee of $110 and GST (at the then rate of 12.5 percent) of $13.75. When GST was increased to 15 percent in 2010, the fee was not adjusted meaning that the fee excluding GST decreased from $110 to $107.60.

18

Under the firearms licensing system, fee recovery is confined to applications for firearms licences, renewals, endorsements and consents for gun shows. There are many other services New Zealand Police provide as part of the firearms licensing system, such as granting permits to import, that are not subject to fee recovery. Approximately 80 percent of firearms licensing fee revenue derived by New Zealand Police comes from application fees for standard licences.

19

New Zealand Police’s 2017–2018 annual report noted that in 2017–2018 the firearms licensing system cost approximately $14 million to run. In the same financial year, $3.63 million was received in firearms licence application fees, leaving New Zealand Police to meet the remaining $10.40 million cost from their budget. The same annual report states “[d]ue to increased demand in other Police priority areas”, fewer resources were “available for licensing activities in the 2017–2018 year”.

20

The effect of this is that the more money spent on firearms licensing, the less New Zealand Police can spend on other areas of operations or projects. It would not be sensible for us to determine whether New Zealand Police “underspent” on firearms licensing because “too much” was spent on other areas, say family violence. What we can say is that the resources able to be committed to firearms licensing were constrained by the failure to increase the fees payable for firearms licence applications. Such fees are set by regulation and change would thus depend on a political decision leading to legislative action (in the form of an amendment to the Arms Regulations).

4.7 Issues with administration

21

Prior to 1992, standard firearms licences were valid for the licence holder’s lifetime. The Arms Amendment Act 1992 reduced this to 10 years. The way this was implemented resulted in what New Zealand Police refer to as the “licensing bell curve”. New Zealand Police receive approximately 13,000 applications annually for two years, followed by a three-year period of approximately 47,000 applications annually, followed by another two-year period of 13,000 applications. The variability in licensing renewals creates a number of issues for New Zealand Police, including pressures on funding and a requirement to hire contract staff to cover the additional workload in the busy years. All of this plainly put considerable pressure on those administering the system. We note that the individual’s application was dealt with in a year of increased applications due to the licensing bell curve. For example, the Southern District – where the individual applied for his firearms licence – processed 5,737 firearms licence applications (including renewals) in 2017 (as compared to 3,159 in 2018).

22

Other administration issues frequently raised by those we spoke to were:

- Licensing processes are paper-based and require extensive double handling with consequent inefficiencies.

- District firearms staff are given limited initial training and, in recent years, no ongoing training and current training standards are outdated and inconsistent across New Zealand Police.

- As the licensing system is operated at a District level, there are significant inconsistencies from District to District.

We deal with each of these points in turn.

23

The firearms licensing process is old-fashioned. It involves paper files, parts of which are sent by mail to Vetting Officers and then returned by mail to the District Arms Officer. There are associated requirements for stapling, unstapling and the use of sticky notes. Such a system is inefficient for firearms licensing staff. As well, it is not susceptible to effective monitoring and performance review. These inefficiencies meant District firearms staff spent a disproportionate amount of time on administrative tasks, at the expense of time available to assess the merits of firearms licence applications.

24

In dealing with interviews of applicants and referees, the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide is prescriptive in terms of the questions that must be asked. But the Arms Manual states:

The points set out in the formats are not exhaustive and vetters are encouraged to ask whatever extra questions they consider are appropriate in each case. There is a danger of interviews becoming stereotyped.

That is sensible advice. However, licensing staff are not trained to go beyond what is in the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide. There are no training opportunities to learn how to better assess difficult and marginal applications. Licensing staff are not trained to say “no” to applications. There was no system of performance review and no mechanism for identifying Vetting Officers whose interviewing practice had become entirely controlled by the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide or, to use the language of the Arms Manual, “stereotyped”.

25

The last issue concerning inconsistencies in the process can be demonstrated by applicants’ perceptions of the intensity of the vetting process and differing approaches to the substitution of a near-relative referee.

26

Some of those who made submissions to us described intense and exhaustive vetting processes, involving interviews extending over several hours, questioning about political and social views, up to six referees being required, medical certificates sought and inquiries made in other countries. Other submitters, however, described processes that were light and in the nature of rubber-stamping.

27

We asked all of the District Arms Officers in New Zealand to describe the process in their District for determining whether an unrelated person who is to be substituted for a near-relative referee knows the applicant well enough to be suitable as a referee. The inconsistencies in practice are demonstrated by the answers below:

- One District Arms Officer told us that in their District the substituted referee must have known the applicant for at least two years.

- One District Arms Officer told us that the substituted referee must have known the applicant for a sustained period – generally three to five years.

- One District Arms Officer told us that it “would be expected that the referee nominated has known the applicant for a minimum of 12 to 18 months along with having had ongoing and regular contact”.

- One District Arms Officer told us that it is “[New Zealand] Police policy that the applicant is to provide a next of kin referee in New Zealand. If the applicant has no next of kin in New Zealand and [New Zealand] Police have no evidence to dispute this, then [New Zealand] Police are required to accept the referee provide[d] by the applicant”.

- One District Arms Officer told us that, in their District, if there is no near-relative the applicant is required to nominate two additional unrelated referees.

- One District Arms Officer told us that it “would typically not be known until the interview was completed”, when the District Arms Officer would review the responses to the vetting questions (including the length of time the referee had known the applicant) to assess whether the referee knew the applicant well enough to provide reassurance that the applicant was a fit and proper person.

4.8 Limited guidance given by the Arms Manual, the Master Vetting Guide and the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide

28

New Zealand Police policy and guidance were tailored to an applicant who had spent all, or a considerable portion, of their life in New Zealand and could provide a near-relative referee and another person who both knew the applicant well and could be interviewed in person.

29

It was recognised that not every applicant would fit this model. To allow for this, a near-relative referee could be substituted with another referee. But there was no attention focused on:

- whether it would be appropriate to conduct a phone or video interview with a near-relative who lived overseas;

- what should happen if a substitute for a near-relative referee, who knew the applicant “best in a personal sense”, did not know the applicant very well; and

- the questions that should be asked of the substituted referee to test the depth of the relationship.

30

As we have explained, one of the purposes of interviewing a referee about their relationship with the applicant is to establish whether the referee knows the applicant well enough to adequately comment on whether the applicant is a fit and proper person to possess a firearm. Unfortunately, the Arms Manual, the Master Vetting Guide and the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide do not identify that this is the primary purpose of that part of the vetting exercise.

4.9 The ease of obtaining a firearms licence

31

A number of people told us that New Zealand Police tend to grant a firearms licence unless there are strong reasons to decline. The suggestion was that it is too easy to obtain a firearms licence. In support of this, reliance is placed on the limited number of refusals. The information we have been provided shows that only 2.1 percent of all new applications for standard firearms licences between 2014 and 2018 were declined by New Zealand Police.

32

Under the Arms Act, a firearms licence is not to be granted unless the relevant member of New Zealand Police is “satisfied that the applicant is a fit and proper person to be in possession of a firearm”. Obviously, it is for the applicant to satisfy the fit and proper person test. There are, however, some complicating factors:

- As noted above, a non-sworn member of Police can grant a firearms licence but only a police officer of the rank of inspector or above may decline one. For those who are working in the system, this might be taken to suggest that refusal of a firearms licence is more significant than a grant and, perhaps, that applications are to be granted unless there is good reason not to.

- There is a practical, if not legal, requirement for administrative decisions, particularly those that are able to be appealed, to be supported by reasons.19

- If an applicant asserts good character, is supported by referees and has no disqualifying factors on their National Intelligence Application profile (such as a history of family violence), a police officer of the rank of inspector or above may have found it difficult to refuse a firearms licence based on the fit and proper person test. One reason could be insufficient evidence from an applicant - for instance, in the case of an applicant who had recently arrived in New Zealand. However, New Zealand Police policy and operational guidance were of limited assistance on this point.

- Adding to this is the case law on firearms licence refusals and revocations. Under section 62 of the Arms Act there was a right of appeal to the District Court against the refusal or revocation of a firearms licence. A number of the judgments dealing with the appeals suggested New Zealand Police had adopted an approach to the fit and proper person test that was too strict.20 These cases generally indicate judicial tolerance for granting or not revoking a firearms licence despite applicants or firearms licence holders (as the case may be) having sometimes serious convictions.21

33

In addition, we would note that the low level of refusals – 2.1 percent of all new applications for standard licences – is not necessarily indicative of a lax approach to granting firearms licences. The firearms licensing process has a gate-keeping role in that applicants who are unlikely to be successful are unlikely to apply. A potential applicant who has, for example, a long history of criminal offending is unlikely to waste the application fee knowing that their application will likely be declined.

34

We are not in a position to assess whether it has been “too easy” to obtain a firearms licence. This would require extensive analysis of a range of material held by New Zealand Police, including application files and the subsequent conduct of those who were granted firearms licences. The licensing process has changed since 15 March 2019. So, the cost of such an exercise in terms of time and money would heavily outweigh the possible benefits.

4.10 Reviews, reports and commentary on the firearms licensing system

35

The 1997 Thorp Report concluded there was “a need for radical reform of the firearms laws”.22 It also noted that the distinction between military style semi-automatic firearms and other semi-automatic firearms had “proved to be problematic at best since 1992” and that “the potential for evasion of the law is too great”.23 Its 60 recommendations included the following proposals:24

- Military style semi-automatic firearms should be banned (with an exemption for people working in animal pest control, if no other firearm would be equally effective for their particular business).

- All other style semi-automatic firearms should be limited to a magazine capacity of seven cartridges.

- The licensing system should be replaced by a combined licensing and registration system based on three-year firearm-specific licences.

- There should be an attempt to define, in consultation with representatives of New Zealand Police, psychiatrists, firearms users and family violence workers, a list of characteristics likely to make a person unsuitable to possess firearms. The list would be used to guide Vetting Officers.

- People who commit certain offences should be disqualified from holding a firearms licence for a set period.

- Two referees should be consulted as part of the vetting process (in all but exceptional cases).

- If there are concerns about the suitability of a firearms licence applicant, New Zealand Police should consult an independent referee.

- An applicant’s mental health information should be able to be shared by health professionals with New Zealand Police, if it would be relevant to a firearms licensing decision.

36

The Thorp Report also recommended that an independent Firearms Authority be established to manage implementation of the Report’s recommendations and to be responsible for the administration of firearms control for either five years or on a permanent basis.25 This was to avoid New Zealand Police’s “ingrained attitudes” in relation to firearms control, which were seen as possibly preventing the recommendations being successfully implemented.26

37

The Thorp Report had little immediate impact. Following the report, New Zealand Police indicated that many of the recommendations were already part of their practices.27 Other recommendations were not accepted because they had “significant financial, policy or legislative implications for Government”.28 Tighter control of semi-automatic firearms did not eventuate. An attempt in 1999 to introduce a firearms register29 did not succeed.30 Similarly, a separate attempt to establish an independent Firearms Authority,31 as proposed in the Thorp Report, failed.32

38

Prior to 15 March 2019, there were other reviews or commentary in relation to the firearms licensing system. In particular, a report produced in 2011 by the Combined Threat Assessment Group titled Availability of Firearms in New Zealand to Terrorists, Violent Extremists and Acutely Disaffected Persons, two New Zealand Police assessments in 2014 The Right-wing in New Zealand: Myth vs Reality and Domestic Extremism: Unlikely but not out of the question, a comprehensive review carried out by New Zealand Police of the management and administration of firearms that was presented to New Zealand Police’s Executive in May 2015, a 2017 Report of the Law and Order Select Committee of Parliament Inquiry into issues relating to the illegal possession of firearms in New Zealand and the 2017 New Zealand Police Briefing to the Incoming Minister.

39

The assessments by the Combined Threat Assessment Group and New Zealand Police are discussed in more detail in Part 8, chapter 4. For present purposes, we note that the Combined Threat Assessment Group identified that a terrorist or violent extremist could legally acquire firearms, including military style semi-automatic firearms, for use in an attack. In addition, New Zealand Police in their 2014 assessments noted the propensity for right-wing extremists to acquire and use firearms. They also concluded that the relative ease of access to semi-automatic firearms in New Zealand meant that a lone actor terrorist attack remained a possibility.

40

The other documents referred to above cover much of the same ground in relation to the firearms licensing system as we have, including the ineffective regulation of semi-automatic firearms and issues with the firearms licensing process.

41

In June 2017, New Zealand Police established the Arms Act Service Delivery Group. The three key areas of opportunity and focus for the Arms Act Service Delivery Group were:

- the need for consistency in how firearms administration is undertaken within and across Districts, including staff training and development of national standards;

- better and more frequent communication and engagement between New Zealand Police and the firearms community; and

- the introduction of digital options and automation to reflect an increasingly digital community, while retaining paper-based options for those who cannot, or prefer not to, use digital channels.

42

The Arms Act Service Delivery Group implemented some changes to the firearms licensing process. For example, in March 2018, a centralised team responsible for granting import permits was established to ensure consistency across the different Districts and, in July 2018, the Firearms Safety Course required to be undertaken by first time applicants was changed to include a practical component. As well, the Arms Regulations were changed to allow electronic filing of applications.

43

In November 2018, the Arms Act Service Delivery Group presented a paper to New Zealand Police’s Senior Leadership Team titled Proposal to change the management and administration of Arms Act. It proposed:

- establishing a service centre model with administration in a central location, and dedicated Arms Officers in Districts;

- managing all firearms administration costs from a single cost centre and enabling (over time) full cost recovery;

- providing dedicated firearms training and review resources to ensure New Zealand Police employees have the skills and knowledge to create trust and confidence in New Zealand Police across the country;

- freeing up senior leaders’ time from administrative work (licence revocation preparation work as an example) to concentrate on staff management and freeing up District Arms Officers to interact with the community rather than sitting at their desks;

- building a modern online application service with workflow and graduated response processing to give a faster and easier application process with no loss of rigour; and

- initiating proactive reviews of firearms community members supported by a robust and consistent revocation process.

44

The paper was largely endorsed by New Zealand Police’s Senior Leadership Team.

45

Beginning in June 2018, the Arms Act Service Delivery Group met with firearms staff, members of the firearms community and iwi representatives across New Zealand to discuss the firearms licensing process. On 29 January 2019, the Arms Act Service Delivery Group produced a consultation document, based on its nationwide discussions, on proposed changes to the operating model and organisational structure for the administration of the Arms Act. The results of the internal consultation were due to be announced in early April 2019. This was postponed following the terrorist attack on 15 March 2019.

4.11 Concluding comments on the firearms licensing system

46

How semi-automatic firearms ought to be controlled is a matter of legislative judgement. For this reason, we take the balance struck by Parliament in 1992 as our starting point. Under this balance, a person holding a standard firearms licence could acquire and possess a semi-automatic firearm providing it lacked certain features and was not fitted with a large capacity magazine. A firearms licence holder required an E Endorsement to lawfully acquire and possess a semi-automatic firearm with a large capacity magazine. But because large capacity magazines could be lawfully acquired without producing a standard firearms licence, let alone one with an E Endorsement, these restrictions were easily evaded. And more generally, the policy of the 1992 amendments of limiting the number of military style semi‑automatic firearms in New Zealand through import controls and the permit to procure requirement had been ineffective.

47

That the distinction between military style semi-automatic firearms and other semi‑automatic firearms was “problematic” and there was the “potential for evasion” were recognised in the 1997Thorp Report, more than 20 years before the events of 15 March 2019. And the potential for a terrorist to use semi-automatic firearms was explicitly recognised in 2011 by the Combined Threat Assessment Group and in 2014 by New Zealand Police assessments.

48

As at 15 March 2019, the firearms licence application fee was $123.75, a level at which it had been fixed since 1999. Under administrative law principles, revenue from fees charged sets a practical base for the funding of the operation of the firearms licensing system. In other words, New Zealand Police could not spend less on firearms licensing than they charged. But the firearms licensing system cost New Zealand Police far more than the revenue it produced, which constrained the resources that were devoted to firearms licensing. So, Vote Police money (funded by the taxpayer) subsidised the administration of the firearms licensing process. Cost recovery was far from complete. In the 2017–2018 year recoveries were $3.63 million against costs of $14 million.

49

The operation of the firearms licensing process was constrained by three external factors:

- the resources available;

- the structure of section 24 of the Arms Act, which created different decision paths for granting and refusing licence applications; and

- the drift of the District Court judgments that were in favour of those challenging refusals or revocations of firearms licences.

50

The firearms licensing process was further affected by the following factors:

- Its paper-based nature.

- The absence of training and performance monitoring of firearms licensing staff responsible for administering the process.

- A failure to ensure that the guidance given by policy and operational documents addressed more than the typical applicants who had lived their lives in New Zealand and had backgrounds that could be easily checked. As a result there was a lack of coherent guidance as to how to deal with those who had only recently come to New Zealand. There was no policy requiring such applicants to produce their criminal history reports from home jurisdictions and no specific guidance to licensing staff on how to apply referee requirements where a near-relative referee could not be interviewed in person.

51

The combined limitations in the guidance provided by the Arms Manual, the Master Vetting Guide and the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide, and the lack of training, meant that those who administered the firearms licensing process were not well-placed to form and apply evaluative judgements in marginal cases. As we will explain in chapter 6 of this Part, this is illustrated by the way in which the individual’s licence application was handled.

14. Sir Thomas Thorp KNZM, footnote 2 above at pages 27–28.

15. Aaron Karp Estimating Global Civilian-held Firearms Numbers (Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia, 2018). See also S Every-Palmer and others “The Christchurch mosque shooting, the media, and subsequent gun control reform in New Zealand: a descriptive analysis” (2020) Psychiatry, Psychology and Law at page 1; and Nathan Swinton A Turning Point for Firearms Regulation: Implications of Legislative and Operational Reforms in the Wake of the Christchurch Shootings (Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy, September 2019) at page 21.

16. New Zealand Police Official Information Act Disclosure IR-01-18-11101 (29 November 2018).

17. New Zealand Police Official Information Act Disclosure IR-01-18-12383 (29 November 2018).

18. Marie Russell and Hera Cook Fact Sheet: Firearms in New Zealand (3 April 2019).

19. We say “practical” requirement because there is no general obligation to provide reasons in New Zealand. See R v Awatere [1982] 1 NZLR 644 (CA); and Lewis v Wilson & Horton [2000] 3 NZLR 546 (CA). The Supreme Court declined to revisit this position in Manukau Golf Club Inc v Shoye Venture Ltd [2012] NZSC 109, [2013] 1 NZLR 285. See Manukau Golf Club Inc v Shoye Venture Ltd [2012] NZSC Trans 14 at pages 2–4 and 14–20. For an analysis of the requirement to give reasons in a judge-alone trial in criminal proceedings, see Sena v Police [2019] NZSC 55, [2019] 1 NZLR 575.

20. For a sample of cases where the decision to refuse or revoke a firearms licence (made by a police officer with the rank of inspector or higher) has been overturned on appeal, see: Jenner v Police, footnote 10 above; Police v Cottle, footnote 9 above; Flynn v Police, footnote 12 above; Mallasch v Police, footnote 11 above; Dobbs v Police [1992] DCR 650 (DC); Gadsby v Police DC Masterton CIV-2012-035-000064, 11 May 2012; Hubber v New Zealand Police DC Invercargill CIV‑2012-025-000501, 8 July 2013; Hore v Police [2017] NZDC 5263; [Park] v Police [2018] NZDC 5946; Lincoln v Police DC Palmerston North 281‑95, 24 November 1995; Twining v Holland DC Pukekohe MA 338-91, 12 August 1992; O’Loughlin v Police [2001] DCR 488 (DC); De Pina v New Zealand Police DC Hamilton CIV-2006-019-000459, 25 August 2006; and Carruthers v New Zealand Police DC Opotiki CRI-2011-047-000050, 12 April 2012.

21. See, for example, Jenner v Police, footnote 10 above, where the applicant had 17 prior convictions for breaches of the Arms Act.

22. Sir Thomas Thorp KNZM Report, footnote 2 above at page 237.

23. Sir Thomas Thorp KNZM Report, footnote 2 above at page 137.

24. Sir Thomas Thorp KNZM Report, footnote 2 above at pages 239–242.

25. Sir Thomas Thorp KNZM Report, footnote 2 above at page 231.

26. Sir Thomas Thorp KNZM Report, footnote 2 above at page 225.

27. Arms Amendment Bill (No 3) 2005 (248-1) (explanatory note) at page 2.

28. Arms Amendment Bill (No 3) 2005 (248-1) (explanatory note) at page 2.

29. Arms Amendment Bill (No 2) 1999 (312-1).

30. Arms Amendment Bill (No 3) 2005 (248-1) (explanatory note) at page 2.

31. Firearms Authority Bill 1999 (290-1).

32. New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (30 June 1999) volume 578 at page 885.