3.1 Overview

1

In New Zealand, many Public sector agencies contribute to the counter-terrorism effort. Each agency is responsible for its own performance and contribution. Leadership and oversight of the collective counter-terrorism effort is not exercised through a single agency or ministerial portfolio.

2

In this chapter we:

- describe political ownership and public engagement in the counter-terrorism effort;

- assess leadership and coordination of the counter-terrorism effort;

- examine strategy and priority setting;

- describe oversight and performance monitoring;

- discuss gaps in the leadership and oversight of the counter-terrorism effort; and

- set out developments since 15 March 2019.

3.2 Political ownership and public engagement

3

Political ownership of, and public discussion on, terrorism risk provide transparency and enhance social licence for the counter-terrorism effort.

4

In New Zealand, prime ministers and ministers actively engage on national security issues that are well recognised by the public, such as natural hazards, biosecurity and border security. They rarely speak publicly about the terrorism threat or violent extremism, and far less so than we observed or were told about in Australia, Norway and the United Kingdom. One senior official told us that ministers “pay attention to national security questions when they’re put in front of them and not otherwise”.

5

In 2014, the government created a new role of minister for national security and intelligence, with responsibility for leading the national security system. This was separate to the existing role of minister responsible for the intelligence and security agencies.43 Then Prime Minister, Rt Hon John Key, made a significant national security speech on 5 November 2014.44 In this speech he disclosed, for the first time, the watch list of 30–40 individuals of national security concern and the terrorism threat level and publicly confirmed that New Zealand was a member of the Five Eyes.

6

In 2016, the then Attorney-General, Hon Christopher Finlayson, undertook public engagement on the Intelligence and Security Bill (see Part 8, chapter 14). This included community hall meetings and visits to masajid.

7

As we will outline in Part 8, chapter 4, ministers and the public generally understood that there was a relatively benign terrorist threatscape in New Zealand. Before the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack, the threat and risk of domestic terrorism (and especially of non-Islamist terrorism) were lightly covered in assessments and policy advice to ministers, such as when the National Security and Intelligence Priorities were approved. For example, the regular intelligence briefs provided by the National Assessments Bureau to the prime minister included little on the domestic extremism or terrorism environment. From 2010 to 15 March 2019, these briefs contained fewer than twenty references to domestic extremism in New Zealand.

8

Overall New Zealand’s relative geographic isolation and the comparative absence of terrorist attacks on New Zealand soil led to low levels of public and official concern about domestic terrorism threats. The overall threat of terrorism in New Zealand was assessed as “low” (terrorist attack is assessed as possible but is not expected) or “very low” (a terrorist attack is assessed as very unlikely) between 2010 and 2018. This perception of the terrorism risk impacted on the pace at which policy decisions were progressed. An example involves the delays in updating relevant legislation (see Part 8, chapter 13).

9

Informed public debate can provide a sense of society’s appetite for activities to address threats to national security. From our inquiries, we are satisfied that agencies have had successes in countering and disrupting terrorism and violent extremism in New Zealand. But these domestic counter-terrorism successes occurred well out of the public eye and their stories have not been told publicly. Instead, we heard that the Dotcom and Snowden controversies (see Part 8, chapter 2) diminished politicians’ interest in promoting public discussions or counter-terrorism initiatives that might include the intelligence and security agencies’ roles.

10

Former and current ministers and senior officials appear to have been concerned that public-facing strategies and public discussion about countering terrorism might have had adverse impacts on communities (particularly Muslim communities), given rise to unwarranted community anxiety or created expectations of mitigations the Government could not provide. In addition, New Zealand was still facing fiscal constraints in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis and the 2010-2011 Canterbury earthquake sequence. As a result of these factors, and the impact of public controversies, ministers have approached any changes to the counter-terrorism effort conservatively.

11

The absence of a widespread or regular national public dialogue on New Zealand’s national security and counter-terrorism effort was raised with us by senior officials, community groups, our Muslim Community Reference Group and in submissions. Several previous reviews highlighted the need for change in this area.45 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet recommended introducing an ongoing public dialogue on national security and counter-terrorism in the 2017 Briefing to the Incoming Minister for National Security and Intelligence. But this did not happen.

12

There was very little engagement between those responsible for the counter-terrorism effort and the public before 15 March 2019. This meant there was not a well-informed public discussion on the terrorism threat and risk, or information on how to identify threats. Before 15 March 2019, there was limited reporting from the public to the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, and such reporting as there was focused largely on suspected Islamist extremists. The same was true of the reporting of possible extremists to New Zealand Police.

13

There was an understandable increase in engagement from the public immediately after 15 March 2019. Public referrals or reports to the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service and to New Zealand Police increased significantly as the public had a greater appreciation of the terrorist threat. Many of these reports involved people on the far right. For example, in the period between 15 March 2019 and the end of May 2019, New Zealand Police received 2326 public reports or referrals, a substantial proportion of which related to people with far right views.

14

Since 15 March 2019, the Government has released more information relating to national security and the counter-terrorism effort. But this has happened quietly, and without a framework to engage the public or encourage diverse views on countering terrorism and violent extremism. For example:

- The National Security and Intelligence Priorities (agreed in 2018) were published for the first time as an appendix to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s 2019 annual report.46 There was no accompanying public announcement. Unsurprisingly, this did not generate public discussion about intelligence collection priorities, despite the increased interest in the counter-terrorism effort after 15 March 2019. In September 2020, the National Security and Intelligence Priorities were published directly on the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s website.47

- A high-level Countering terrorism and violent extremism national strategy overview was published on the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s website in February 2020.48 Again, this was not promoted as an opportunity for, and thus did not generate, wide public discussion.

3.3 Leadership and coordination

15

In this section, we discuss leadership and coordination roles within New Zealand’s national security system and the counter-terrorism effort. As will become apparent, there is some lack of clarity about leadership of the different parts of the counter-terrorism effort and no one agency is currently responsible for monitoring overall system performance.

A decentralised coordinated model

16

New Zealand’s counter-terrorism effort is decentralised but coordinated. It is decentralised in that no single agency has overall responsibility for the effort. Instead, it is spread across multiple agencies, with each agency responsible for its own performance and contribution. Coordination comes from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. It does not have directive control over the individual agencies or their contribution to the overall work programme.

Figure 40: Counter-terrorism functions of Public sector agencies involved in the counter terrorism effort

17

This model reflects the decentralised approach to the national security system as a whole (see Part 2, chapter 4). The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet told us that centralised responsibility for the national security system is not necessarily a preferred outcome:

Operating as a system, and exercising collective leadership over the national security choices that must be made, does not imply collective accountability for all outcomes. Particularly in a system of government such as that operating in New Zealand, it is not possible to centralise everything. Agencies must know where their accountabilities are, and own these.

18

The government has identified some weaknesses with how decentralised models of accountability and governance work in the New Zealand Public sector. In August 2020, the Public Service Act 2020 was enacted to address some of these deficiencies. The Act has introduced mechanisms to facilitate collective responsibility and accountability for multi-agency programmes of work. We come back to this later in Part 10: Recommendations.

The role of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

19

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet is the lead Public sector agency on national security. Its role is to coordinate activity across the relevant Public sector agencies involved in the national security system. Its chief executive is the “lead official for the whole National Security System” and chairs the Officials’ Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination when New Zealand is faced with a national security event. It is also responsible for coordinating government action in response to national security events, ensuring national security risks are managed appropriately, leading policy development on national security matters, hosting the National Assessments Bureau and administering the Intelligence and Security Act 2017.

20

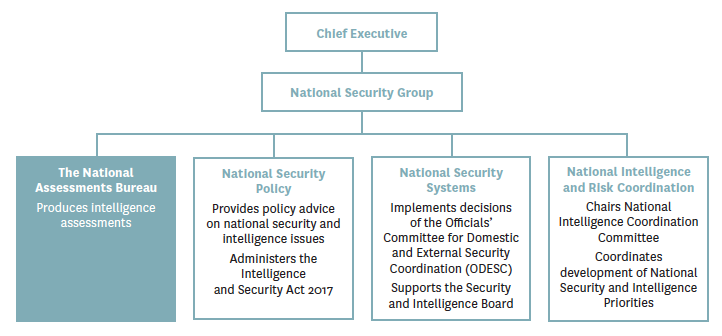

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s current organisational structure for its counter-terrorism functions is outlined in the graphic below.

Figure 41: Counter-terrorism functions within the organisational structure of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

21

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet has a limited legislative mandate for national assessments but otherwise has no directive authority or statutory mandate for its coordination of the national security system or counter-terrorism effort. The relevant agencies and chief executives each exercise their own statutory responsibilities and functions, which are not controlled by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s direct relationship to the prime minister creates a convening power across all Public sector agencies.

22

We were told that other agencies are uncomfortable if the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet is seen as too assertive on national security matters. Howard Broad, former Deputy Chief Executive of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, told us that when he explicitly raised the question of monitoring the intelligence and security agencies’ performance at the Security and Intelligence Board, “there was strong pushback by the agencies and [they] generally agreed around the table that wasn’t the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s role”. He said that, on a practical level, “no-one was indicating a desire that the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet increase its capability”.

23

We also heard that successive prime ministers were not willing to seek additional funding for their own department (especially when they were calling for fiscal control by other ministers). Nor would they support a budget bid through another minister advocating investment for the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet to coordinate national security responsibilities. The result is that the coordination role has not been well resourced.

24

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet advised us that “[its own] investigations have not uncovered any policy or internal papers prepared by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet which explicitly and exclusively deal with the question of its role in the national security system and work priorities directly associated with this”. In its 2018-2019 Business Plan, the National Security Group in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet did note that:

…a strategic refresh is needed. [It is] time to refine the purpose, goals, roles and responsibilities [of the National Security Group].

25

This work had not been completed by 15 March 2019.

The Security and Intelligence Board

26

The Security and Intelligence Board is one of two governance boards that bring together the chief executives of agencies with national security responsibilities (see Part 2, chapter 4). The Security and Intelligence Board focuses on threats from human sources, such as terrorism or foreign interference. The other governance board, the Hazard Risk Board, focuses on threats from non-human sources, such as natural hazards, biosecurity threats and pandemics.

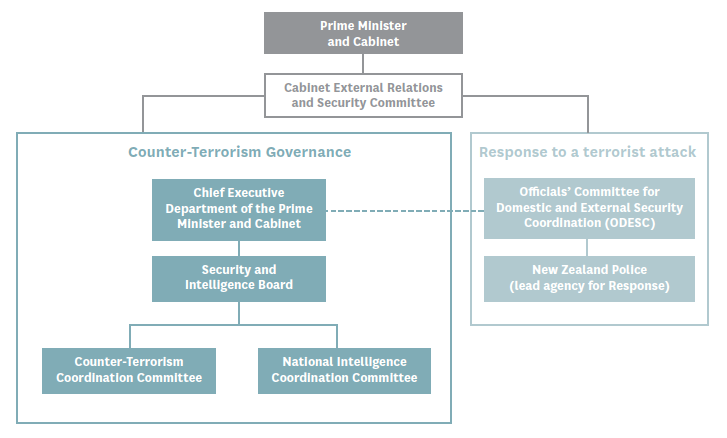

Figure 42: Governance of the counter-terrorism effort

27

Security and Intelligence Board membership includes the chief executives of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Chair), the Government Communications Security Bureau, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, New Zealand Customs Service, the New Zealand Defence Force, New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Other chief executives may be invited by the Chair to attend meetings if required. The Security and Intelligence Board reports to the Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee.

28

The role of the Security and Intelligence Board has evolved following various reviews. Its 2017 Terms of Reference identified its vision as “a resilient New Zealand against those who would wish us harm” and its purpose as to:

Lead, build and govern the security and intelligence system that:

- Identifies and understands threats, patterns and risks in our environment;

- Prioritises vulnerabilities and threats and understands the desired end state to be obtained;

- Hold[s] system to account for delivery:

- Governance of the “[Security and Intelligence Board] deputies group” to implement [the Security and Intelligence Board’s] vision;

- By tracking tasking – ensuring there is a plan that is achievable;

- Enabling of the system wide support of tasking;

- Reporting to [the National Security Committee / Officials’ Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination] as required;

- Build[s] system capabilities and capacity:

- Identifying gaps and weaknesses;

- Developing system policies and processes;

- Reviewing and learning; and

- Remain[s] alert to current threats and opportunities; proactive testing of the plan against “real life information” and events and be agile and responsive.

29

The Security and Intelligence Board’s deliverables include the National Security and Intelligence Priorities, an annual strategic assessment of the environment and action plans to identify threats, patterns and risks.

30

The chief executives on the Security and Intelligence Board each have statutory functions that are not controlled by the Security and Intelligence Board. They each report to their respective ministers and exercise their own responsibilities.

31

Although its Terms of Reference include “hold[ing the] system to account for delivery”, the Security and Intelligence Board does not monitor the performance of the counter-terrorism effort and has not put in place a performance framework and standards for it. It has also not established a system for monitoring its own performance. A 20 June 2019 report to the Security and Intelligence Board noted that work had not yet commenced on measuring or assessing its own governance and coordination performance, the authorising environment (including social licence, transparency and legislation) or relationships (including Five Eyes and other international relationships).

32

The Security and Intelligence Board has several subcommittees. The two subcommittees most relevant to the counter-terrorism effort are:

- the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee, which provides advice to the Security and Intelligence Board on counter-terrorism systems, priorities, risks, projects and resourcing requirements; and

- the National Intelligence Coordination Committee, which coordinates the delivery of the National Security and Intelligence Priorities, and the work programmes of the assessment agencies (see Part 8, chapter 4).

Leadership of the counter-terrorism effort

33

It is important that all agencies in the counter-terrorism effort are guided by a clear understanding of who does what, when, why and how across the 4Rs – Reduction, Readiness, Response and Recovery activities (see Part 2, chapter 4).

34

The government’s Counter-Terrorism Playbook49 states that New Zealand Police are “the designated lead agency, providing command and control of the multi-agency response to any [terrorism] event in New Zealand”. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet has publicly stated that “New Zealand Police are well prepared and exercised to lead the response to a terrorism incident”. So the lead agency for Response to a terrorism terrorist event incident is clear.

35

We did not, however, observe a similar consensus on which Public sector agency leads Reduction, Readiness and Recovery activity.

36

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet told us that it, together with New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, had been identified as the risk coordinating agencies for terrorism since the beginning of the development of the National Risk Register framework in 2015 (see 3.4 Setting the strategy). In contrast, the Security and Intelligence Board’s December 2018 report on Better Management of National Security Risks identified New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service as the risk coordinating agencies, but not the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

37

The National Security Handbook refers to New Zealand Police as the lead agency for counter-terrorism at both the national, local and regional levels, suggesting it is the lead agency for all of the 4Rs. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet considers “[New Zealand] Police are the lead agency for all ‘4Rs’ of the Terrorism risk, but that several parts of risk management and the [Counter-Terrorism Work Programme] are led by other agencies coordinated by [the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee] and governed by the Security and Intelligence Board”.

38

In 2016, the Security and Intelligence Board discussed the overarching leadership of counter-terrorism in New Zealand and considered identifying New Zealand Police as the lead. In the associated discussions there was recognition of the significant additional burden this would place on New Zealand Police and the absence of a lead minister for counter-terrorism. In the end, there was no decision on this and leadership remained with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

39

In October 2016, the role of Specialist Coordinator was created within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet to provide system-level coordination of collective counter‑terrorism activity through the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee, and support the Security and Intelligence Board and Cabinet National Security Committee governance functions. When it was created, the Specialist Coordinator role was expected to be responsible for “driving delivery of a co-ordinated, cross-agency programme that strives to eliminate gaps and minimises the likelihood and impact of terrorist threats to New Zealand”. It was expected that the creation of this role would ensure that “the [Counter-Terrorism Work Programme] can respond in a timely manner to changing risk”. As chair of the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee, the Specialist Coordinator would work with senior officials from agencies with key counter-terrorism responsibilities, including those involved in social cohesion and preventing violent extremism. After the role was filled, a high-level Counter-Terrorism Work Programme was developed and reported to the Security and Intelligence Board in July and September 2018. The Specialist Coordinator was the only coordinator appointed for a specific national security threat before 15 March 2019.

40

Evidence provided to us indicates there continues to be different understandings and expectations about where leadership of the counter-terrorism strategy and the counter-terrorism effort sits, and what that means in practice:

- A former Specialist Coordinator at the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (who chaired the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee) considered it more important that the Security and Intelligence Board had overall responsibility for collective counter-terrorism responsibilities rather than one agency. This is because backing from multiple agencies is needed to deliver the counter-terrorism effort.

- The Government Communications Security Bureau suggested that domestic counter-terrorism efforts are co-led by New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, as the domestically-focused law enforcement and intelligence and security agencies.

- Rebecca Kitteridge, Director-General of Security, told us the overall lead for counter-terrorism is the Specialist Coordinator in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, as that agency can look “end to end” from social inclusion right through to prosecutions and has the coordination and policy function needed for this. She expressed concern that there had not been a proper analysis put forward when New Zealand Police were proposed as the lead. She also noted that while New Zealand Police have a wide reach into communities they are not a policy agency and, as an operational agency with a law enforcement mandate, they were not best placed to lead at the softer end of counter-terrorism activities, such as social inclusion and countering violent extremism.

- The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service advised that it does not consider itself the “lead agency for the national counter-terrorism effort”, but rather that it has the lead responsibility for “counter-terrorism security intelligence investigations, analysis and reporting”.

- A current senior manager at the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service thought the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet is best placed to lead the “practical … day-to-day” counter-terrorism system because it can see across sectors and agencies and houses the Specialist Coordinator. They thought the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet does not currently play that role and no one agency does.

- Mike Bush, former Commissioner of Police, told us he did not see the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet as the counter-terrorism lead. He said the lead could be, and currently is, held jointly by New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, but that clarity of their roles and responsibilities is essential.

- Andrew Kibblewhite, former Chief Executive of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, suggested many agencies had a part to play (for example, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet for coordination, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service via the Combined Threat Assessment Group for assessing risk and New Zealand Police for Response).

41

Some of the opinions expressed above take a broad view of the definition of counter-terrorism, one that includes measures such as social inclusion (see Part 9: Social cohesion and embracing diversity). But even with that acknowledgement, the different views expressed above show that there is no common understanding about leadership of the counter-terrorism effort and what it means in practice.

3.4 Setting the strategy

42

Within the New Zealand public sector, multiple Public sector agencies often contribute to a single programme of work. In this situation it is common to create a strategy to clarify roles and responsibilities and coordinate, prioritise and align agencies’ work.

43

In this section we discuss efforts to develop a counter-terrorism strategy, an approach to national risk management and priorities for collection and assessment of national security intelligence.

Counter-terrorism strategy

44

The need for a counter-terrorism strategy has been highlighted in a number of reviews. In 2013, Counter-Terrorism: A review of the New Zealand CT landscape noted that “New Zealand does not have an overarching policy document describing our national approach to counter-terrorism” and that “in the main, agencies are left to their own judgement with respect to the activities they embark upon with respect to reducing the risk of terrorism”.50 Also in 2013, the Review of Arrangements for Coordinating National Security and Intelligence Priorities recommended that a national strategy should be urgently completed to “provide a single set of organising principles for the national security system to prioritise and plan”.51 While this point was made about the lack of a strategy for the national security system, it also applies to the lack of a counter-terrorism strategy.

45

A 2015 report reiterated the need for a New Zealand counter-terrorism strategy. That report identified an insufficient emphasis on risk assessment, the absence of formalised arrangements that enabled ministers to weigh up the violent extremist or terrorist risk against other national security risks and the lack of whole-of-government counter-terrorism work programme management, reporting or evaluation. It also identified the continued absence of planned and regular public engagement on the terrorism risks facing New Zealanders at home and abroad and measures taken to counter those risks.

46

Following this advice, Cabinet agreed in 2015 that the minister responsible for the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service and the Government Communications Security Bureau would lead public engagement on, and represent, the broader counter-terrorism work programme (which included the Department of Corrections, the Department of Internal Affairs, the Government Communications Security Bureau, Immigration New Zealand, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Ministry of Justice, New Zealand Police, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service and the Office of Ethnic Communities). Later that year, Cabinet directed officials to report to ministers with advice on the development and release of a public counter-terrorism strategy and public engagement plan.

47

In July 2016, the Security and Intelligence Board recognised the “urgent need for agencies to [sort out] New Zealand’s counter-terrorism arrangements in line with ministerial expectations” and noted the continuing absence of an overarching strategy for counter-terrorism.

48

A Counter-Terrorism Strategic Framework was approved by the Security and Intelligence Board in 2018. This was not a detailed, comprehensive strategy document. It was a two page document intended to “support directional alignment across agencies and to act as a tool for supporting articulation of our [counter-terrorism] system”. Its primary audience was not the public. It had not been developed in consultation with non-government parties. It did not assign leadership and responsibility to specific Public sector agencies for counter-terrorism prevention and Reduction activity. This was the only contemporary document guiding the counter-terrorism effort before 15 March 2019.

49

Although the agencies continued to support the development of a national counter-terrorism strategy, a strategy had not been adopted before 15 March 2019. A senior official spoke of their frustration with how long it has taken to develop a counter-terrorism strategy. They were also frustrated at the low prioritisation of counter-terrorism compared to other important national security issues such as pandemics and people smuggling.

50

As explained in Part 2, chapter 4, counter-terrorism activities have expanded to include Reduction activities to counter violent extremism. These activities range from early intervention programmes targeting those showing signs or vulnerabilities to radicalisation, through to community-based activities aiming to prevent the emergence of violent extremism by building social inclusion.

51

Before 15 March 2019, there were some activities underway that aimed to reduce the risk of violent extremism, such as the Young Person’s Intervention Programme (see Part 8, chapter 6). We heard that Reduction had received little attention at the Security and Intelligence Board despite urging from some agencies and community groups (see Part 9: Social cohesion and embracing diversity for a description of efforts by community groups). There was progress in September 2018 when the Security and Intelligence Board agreed to a High-Level Framework for the Prevention of Violent Extremism. This encompassed both the development of a multi-agency intervention programme providing tailored support to people at risk of violent extremism (building on the Young Person’s Intervention Programme) and wider cross-agency efforts to promote social inclusion and diversity.

52

The High-Level Framework for the Prevention of Violent Extremism recognised that tension can arise when social inclusion is used as a tool for countering violent extremism, because it can risk stigmatising and alienating communities, thereby undermining social cohesion efforts. The focus was therefore on interventions with people who were noticeably at risk of engaging in violent extremism. It included broader efforts to build:

… strong, trust-based relationships with communities through proactive, broad-based engagement – ideally led by agencies with an enduring community presence and cultural capability. These relationships can then be accessed to engage on specific violent extremism issues in a targeting way if and where they arise.

53

Progress was made in developing the multi-agency intervention programme. But the lack of specificity in what was being proposed for broader community engagement efforts meant that it was not clear what actions were to be taken, by when and by whom. There did not appear to be any consultation with community groups in the development of the High-Level Framework for the Prevention of Violent Extremism.

National Risk Management

54

In September 2015, after engaging with an expert panel, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet produced a report recommending an approach and methodology for developing a National Risk Register. There was broad ministerial and interagency agreement for the development of a National Risk Register.

55

A 2016 report by the Auditor-General recommended that the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet should improve governance of national security risks (especially to provide better definition and clearer accountabilities of risk governance and management).52 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet responded to this in 2016 by developing a risk framework.

56

By November 2016, over 30 Public sector agencies had undertaken indicative risk assessments and considered existing agency risk management arrangements across the 4Rs. These agencies identified gaps and connections, developed some credible event scenarios, and assessed the likelihood and potential impacts of these events occurring over the next five years.

57

In June 2017, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet established the National Risk Unit to develop a National Risk Register. The first draft National Risk Register was produced in August 2018. It comprises approximately 40 risk profiles, including the Terrorism Risk Profile, each of which includes a description, rating and risk management measures. Although not approved by ministers, the draft National Risk Register has been informally adopted by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and shared with Public sector agencies to be used as part of their agency planning and their development of risk mitigation processes.

58

Following informal discussions with ministers in late 2018, officials recommended the release of the National Risk Report (a high-level summary of the National Risk Register) in January 2019. Officials suggested the audience for the National Risk Report would be key decision-makers in public and private organisations, including central and local government agencies, essential utilities and infrastructure providers. Officials suggested that its purpose would be to build public understanding and facilitate an open and transparent public debate about national risks. Despite strong recommendation from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, ministers did not agree to authorise public release of the National Risk Report.

59

In December 2018, officials recommended to the Security and Intelligence Board several changes to terrorism risk management across Reduction and Response activities. These included the introduction of a new annual strategic risk management cycle, commencing with a Combined Threat Assessment Group terrorism threat assessment (see Part 8, chapter 4). The first annual Combined Threat Assessment Group terrorism threat assessment was produced in December 2019 but was not publicly released. Officials also recommended elevating the responsibility for setting the New Zealand terrorism threat level from the Head of the Combined Threat Assessment Group to the Director-General of Security. This change occurred in mid-2019.

The government’s priorities for national security intelligence

60

Two reviews into the intelligence system in 200953 recommended setting clear intelligence collection priorities for all agencies involved in collecting intelligence for national security purposes.

61

Before 2012, the Government Communications Security Bureau operated to requirements for collecting foreign intelligence set by the old Domestic and External Security Coordination system and endorsed by the Cabinet Committee of the same name.54 Other Public sector agencies involved in intelligence collection initially did not have similar set requirements.

62

In 2012 the first National Intelligence Priorities were developed for intelligence collection and assessment, and ranked to guide the level of effort. In 2012, counter-terrorism was set at a medium intelligence priority, as the threat of terrorism (as assessed by the Combined Threat Assessment Group) was “very low”. At the time, the Officials’ Committee on Domestic and External Security Coordination noted that the government’s priorities “will be supplemented by more specific papers to be approved at officials’ level (the national intelligence priorities papers)”. The National Intelligence Priorities were expected to be reviewed every two years.

63

By March 2015, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet had prepared a revised process for the continual review and updating of New Zealand’s National Intelligence Priorities and advised that it would work with partner agencies to “translate these high-level questions into agency-specific actions”. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet recognised that this was needed in the absence of “an explicit overarching strategy for New Zealand’s intelligence community”.

64

In September 2015, ministers agreed 16 National Intelligence Priorities to replace the 2012 Priorities. The Priorities were in three groupings. Terrorist and violent extremist threats to New Zealanders at home and abroad were included in the high priority grouping. Ministers expected these National Intelligence Priorities would be used by chief executives to align the focus of intelligence sector efforts, prioritise work and reallocate additional resources when required. The associated Cabinet paper recorded expectations that the Priorities would support any specific warrants or other ministerial approvals required and ensure active sharing of information, expertise and resourcing across the New Zealand intelligence sector. They directed officials to “report back to Ministers in March 2016 on progress by the [wider intelligence sector agencies] in implementing the intelligence priorities, before the first annual report due to ministers in June 2016 on the performance of the intelligence sector delivering the priorities”. This reporting back did not occur.

65

The Security and Intelligence Board agreed that the National Intelligence Coordination Committee would be responsible for the delivery of the Priorities overall and that it would focus on the top nine of the 16 Priorities (to set the intelligence requirements for assessment and collection). Eleven cross-sector intelligence Priority Coordination Groups were established, each with a coordinator. However, in October 2016 the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet reported to the Security and Intelligence Board that the “national intelligence priorities do not yet fully inform agency priority and planning processes”. It was also reported that the Priority Coordination Groups had delivered mixed results, as there was:

- neither a clear mechanism to provide assurance that customer requirements are being clearly communicated nor a consistent framework to assess progress or gaps;

- no coordinating mechanism to support better measurement of resource allocation and outputs against each National Intelligence Priority; and

- no comprehensive framework to underpin any future queries about New Zealand Intelligence Community collection against specific issues or targets.

66

Faced with these problems, some Public sector agencies developed their own internal prioritisation guidance. For example, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service compensated for this lack of clarity by developing its 10-Year Operational Strategy in 2016.55 This resulted in the establishment of a strategic analysis function (see Part 8, chapter 5).

67

In 2017, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet advised the Security and Intelligence Board that the intelligence prioritisation and coordination frameworks were not doing what they were designed to do. Following a new cross-agency process led by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee approved 16 equally-weighted National Security and Intelligence Priorities in December 2018. The paper seeking Cabinet approval of the new National Security and Intelligence Priorities noted that the Priorities would not prescribe how different agencies should implement their intelligence work plans. The paper observed that the actual level of an agency’s ability to deliver on the Priorities depends on legislation, resourcing and capability. Also in December 2018, the Security and Intelligence Board agreed to disestablish the Priority Coordination Groups and replace them with a new system for delivering the National Security and Intelligence Priorities, facilitated by Sector Coordination Groups.

68

Despite their revised name, the National Security and Intelligence Priorities remain priorities for intelligence collection and assessment. An organising framework identified three types of intelligence and assessment effort and provided guidance on the relative focus for each of the priorities. These were:

- the priorities where specialised secret intelligence collection capabilities can add value (this included terrorism);

- the priorities where broader intelligence activities across a range of Public sector agencies are needed; and

- the priorities where intelligence activity focuses on reporting and assessment, rather than significant New Zealand intelligence collection.

69

The 2012 and 2015 National Intelligence Priorities were expected to lead to prioritised areas of work and resources.56 The 2018 National Security and Intelligence Priorities were not designed to guide day-to-day operational and longer-term strategic decisions of the intelligence and security agencies or the other Public sector agencies involved in the national security system.

70

We were told that the National Security and Intelligence Priorities may be used by some agencies as a point of reference but their high-level nature means they are not helpful for providing guidance on how to prioritise both within and across the Priorities (for example, foreign interference versus terrorism). We were also told that the 2018 restructure of the National Security and Intelligence Priorities into an equally-weighted alphabetical list made them less clear as priorities and few Public sector agencies appear to have incorporated the Priorities into their organisational plans.57

71

The Government Communications Security Bureau and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service interpreted the National Security and Intelligence Priorities as the “government priorities” under the Intelligence and Security Act (see Part 8, chapter 14), setting the outer parameters of their intelligence activities. Beyond that, their relevance is unclear. In a 2018 internal document, New Zealand Police expressed concerns about the costs of participating in the development of the National Security and Intelligence Priorities. They also had concerns about the “poor targeting of the performance framework”.

72

The first three Sector Coordination Groups were established in February and March 2019 for the Priorities of foreign interference, Pacific regional security, and malicious cyber activity. Since 15 March 2019, responsibility for coordinating the terrorism National Security and Intelligence Priority is exercised jointly by the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee and the National Intelligence Coordination Committee.

The 2018 terrorism National Security and Intelligence Priority

73

The terrorism priority approved in December 2018 focused Public sector agencies on domestic as well as international terrorism threats. The domestic terrorism threats were described as “those that may arise in and against New Zealand or be carried out by New Zealanders overseas … [and the] scope includes emerging trends and characteristics associated with overseas terrorist networks’ links to New Zealand”. The international terrorism threats were described as “threats against New Zealand’s interests overseas in areas that have the greatest exposure for New Zealanders, and the trends and characteristics of emerging regional and global terrorism threats” which may impact on New Zealand. We note that the concepts “domestic terrorism” and “international terrorism” are used in ways which appear to differ from our glossary definitions.

74

This characterisation of terrorism as pervasive and not constrained by geographic distance and national boundaries was also reflected in the 2018 Counter-Terrorism Strategic Framework, which stated that terrorism is a threat that “New Zealand actively confronts, both globally and at home”.

3.5 Performance monitoring and oversight

Performance monitoring

75

Several reviews of components of the national security system (see Part 8, chapter 2) have highlighted the light-touch approach to performance monitoring as an issue that should be addressed.58

76

The 2011 New Zealand’s National Security System review stated that “given the significant spending on national security, government needs to ensure that it is achieving its goals in the most efficient manner possible”.59 Similarly, the 2014 Performance and Improvement Framework review stated that:

… the performance challenge for the [New Zealand Intelligence Community] is to clarify the scope of its role and then to create more seamless collaboration and efficient resource allocation amongst individual agencies … . In setting national security priorities and determining the scope of the [New Zealand Intelligence Community’s role], there should be a set of practicable and measureable targets … against which the sector’s performance can be assessed.60

77

In 2017, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet was working on a full set of performance measures for delivery of the National Intelligence Priorities approved in 2015 and updated in 2016. It advised the Security and Intelligence Board that there were still no measures to demonstrate impact. It noted that one of the factors “stopping intelligence and assessment about the national intelligence priorities from informing decision-making and policy-making to the fullest extent” was that:

… current priority descriptions are not clear enough, and don’t provide enough guidance around what areas are of most importance within the priority, why they are important and what outcomes are sought. This also inhibits the development of an effective performance framework.

78

We also observed that performance measures (as recorded in some agencies’ annual reports) were subject to change between years.

79

The current position is that there is still no performance framework in place to measure the efficiency and effectiveness of New Zealand’s intelligence community or counter-terrorism effort, or their delivery against the National Security and Intelligence Priorities.

The role of the central agencies

80

In the New Zealand Public sector, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission (formerly the State Services Commission) and the Treasury are collectively called the central agencies.

81

Central agency oversight has involved a focus on advising chief executives how to achieve system-wide leadership and system results. The efforts of the central agencies, particularly Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, have concentrated on removing barriers to good performance and encouraging relevant parts of the Public sector to work together.

82

The Public Service Commissioner has had an oversight role in relation to leadership and governance of the intelligence and security agencies since the enactment of the Intelligence and Security Act. The Public Service Commissioner’s functions include acting as the employer of chief executives and reviewing the performance of departments. This involves considering the overall performance of the chief executive and the agency. It may also include specific matters for performance development and feedback, as agreed with the chief executive, but does not extend to an ongoing assessment of the operational decisions of the agencies. An Assistant Commissioner at Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission told us it was not the role of Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission to monitor the collective performance of the counter-terrorism agencies nor the Public sector agencies involved in the counter-terrorism effort.

83

A senior manager at the Treasury advised that while the Treasury monitored the financial performance of Public sector agencies (at the appropriation level), it does not monitor the outcomes or outputs that agencies produce with this funding. The Public Finance Act 1989 makes chief executives responsible for what is achieved with their resources.

84

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet advised that it is “not its role or mandate to monitor national security and intelligence sector agencies’ performance against [the National Security and Intelligence Priorities]”, rather it is interested in “how the sector performs in relation to collectively providing intelligence and assessment to support decision-making”. This includes the counter-terrorism effort.

Oversight by the Office of the Auditor-General

85

The Office of the Auditor-General carries out annual audits of Public sector agencies’ financial reports. The Auditor-General is usually responsible for auditing the performance of Public sector agencies to examine their efficiency and effectiveness. Performance audits provide the public with independent assurance that Public sector agencies are delivering what they have been asked to and are operating lawfully.

86

Under the Public Finance Act 1989, Public sector agencies must provide financial and performance information to the Auditor-General at the end of each financial year for audit.61 But the intelligence and security agencies are not required to provide end-of-year performance information to support the annual appropriations (funding) legislation.62 The Office of the Auditor-General has interpreted this to mean that the intelligence and security agencies are excluded from the Public Finance Act requirement to provide performance information for audit by the Auditor-General. The Treasury has confirmed this interpretation. The Auditor-General does not, therefore, audit the performance or operational effectiveness of the intelligence and security agencies.

Oversight of the intelligence and security agencies

87

Significant oversight of the Government Communications Security Bureau and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service is specified in the Intelligence and Security Act.

88

Because the Intelligence and Security Act gives broad powers to the Government Communications Security Bureau and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service to fulfil their functions and objectives, robust and multi-layered oversight is important. The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security and the Parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee are the primary external oversight mechanisms for the Government Communications Security Bureau and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Both of these oversight bodies were established by legislation in 1996 and are now governed by the provisions of the Intelligence and Security Act (see Part 8, chapter 14 for more information on the oversight roles of these bodies).

3.6 Developments since 15 March 2019

89

Cabinet approved a high-level Countering terrorism and violent extremism national strategy overview in September 2019, which was published on the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s website in February 202063. It:

- identifies broad, thematic counter-terrorism activities focusing on Reduction but also includes Readiness, Response and Recovery;

- identifies the importance of public engagement and a public information plan; and

- recognises the linkage to social cohesion activities.

90

It was not developed in consultation with communities, local government and the private sector.

3.7 Gaps in the leadership and oversight of the counter-terrorism effort

Lack of political ownership and informed public debate

91

There has been limited political ownership of, and public discussion on, the threat and risks of domestic terrorism in New Zealand. And the overall counter-terrorism effort is not well understood by most ministers, other politicians, the wider public service or the New Zealand public.

92

Any public discussion has largely focused on controversies that have caused embarrassment for intelligence and security and law enforcement agencies (see Part 8, chapter 2). The few public-facing documents produced about the counter-terrorism effort are not particularly revealing and did not actively engage the public. This means there has been little informed public debate about the threat of domestic terrorism, what is done on behalf of the public by the Public sector agencies involved in the counter-terrorism effort and how the public can contribute.

Absence of strategic analysis and advice across the counter-terrorism effort

93

Good Public sector management practice includes following and implementing relevant regulatory frameworks, existing policy, operational guidance and administrative procedures in ways which give effect to their intended purposes.

94

In addition, the public service has a duty of stewardship to look ahead and provide advice about future challenges and opportunities New Zealand faces. It is the responsibility of chief executives to steward their agency’s capability, and capacity to offer free and frank advice. This involves providing proactive advice on emerging problems, vulnerabilities and opportunities for policy performance improvement. In many New Zealand Public sector agencies, these functions are exercised by strategic policy teams.

95

It is not clear who holds responsibility to look across the counter-terrorism effort to identify such risks and gaps and provide advice to ministers. Although the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet has a national security policy team, it does not exercise this role. Despite this role being in the Security and Intelligence Board’s Terms of Reference it has not carried it out (see 3.3 Leadership and coordination). The assessment agencies provide ministers with intelligence products, but they stop short of providing advice on what to do about the risks or opportunities that may be identified in those products. That responsibility falls on the policy or operational agency relevant to the specific issue (see Part 8, chapter 4). This is due to a separation of assessment from policy making. We heard from one minister that they were surprised and frustrated by this arrangement and that the effect was that ministers received threat assessments without proposed policy or operational responses.

96

The minutes of the Security and Intelligence Board and the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee do not demonstrate that these interagency coordinating groups were working together to provide collective insights from assessments.

Limited availability of external advice

97

New Zealand’s National Security Handbook observes that “local government, quasi-government agencies, and the private sector have increasingly important roles in the public sector”. Think tanks focused on national security issues are an example of such “quasi-government agencies”. They are an established feature of the national security landscape overseas. Such organisations can encourage and inform public debate, facilitate interaction between the private and public sector and offer contestable external advice to government and Public sector agencies.64

98

We did not observe similar relationships between the New Zealand national security system and think tanks in relation to counter-terrorism. Although there are think tanks in New Zealand that focus on national security issues, such as the Centre for Strategic Studies, they do not appear to be utilised by Public sector agencies involved in the counter-terrorism effort in the ways that such bodies are in other countries.

No system-level standards or performance monitoring

99

There is no framework for setting system-level performance standards and accepted best practice for the counter-terrorism effort. This means there is no way to monitor performance or measure the effectiveness of the counter-terrorism effort as a system or to hold Public sector agencies to account if their contributions do not meet the standards.

3.8 Concluding comments

100

Leadership and coordination of New Zealand’s decentralised counter-terrorism effort is non-directive. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s leadership role was never more than coordination of the multi-agency counter-terrorism effort.

101

Between 2014 and 2019 progress was made:

- A new ministerial portfolio for national security and intelligence was created in 2014.

- The Specialist Coordinator for the counter-terrorism effort was appointed in 2016.

- The Intelligence and Security Act 2017 was passed, which reformed the intelligence and security agencies’ authorising environment.

- A National Risk Register was developed in 2018. While the Register has not yet been approved and published by the government, the risk profiles are being used by officials to support a more strategic and proactive approach to risk management.

- A more clearly defined interagency counter-terrorism work programme was progressed by the Security and Intelligence Board in 2018 (largely driven by the Specialist Coordinator).

- The Security and Intelligence Board approved the Counter-Terrorism Strategic Framework and the High-Level Framework for the Prevention of Violent Extremism in 2018.

102

However, there have been significant challenges and, as just described, there are gaps in the leadership and oversight of the counter-terrorism effort that have yet to be addressed.

103

In later chapters we will discuss how this has played out in practice, in particular between the counter-terrorism agencies as to their respective roles and coordination of activities, online capability, target discovery and information sharing.

43. Rt Hon John Key National Security and Intelligence role created (6 October 2014) https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/national-security-and-intelligence-role-created.

44. Rt Hon John Key Speech to NZ Institute of International Affairs (6 November 2014) https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/speech-nz-institute-international-affairs-0.

45. Office of the Controller and Auditor-General Managing Threats to National Security (October 2003); Performance Improvement Framework, footnote 42 above; Hon Sir Michael Cullen KNZM and Dame Patsy Reddy DNZM, footnote 38 above.

46. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Annual Report 2018/2019 for the year ended 30 June 2019 (October 2019) https://dpmc.govt.nz/publications/annual-report-2019.

47. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website National Security and Intelligence Priorities https://dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/national-security-and-intelligence/national-security-and-intelligence-priorities.

48. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Countering terrorism and violent extremism national strategy overview (undated) https://dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2020-02/2019-20%20CT%20Strategy-all-final.pdf.

49. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Counter-Terrorism Playbook (2019) at page 40.

50. Simon Murdoch, footnote 9 above at page 26.

51. Jacki Couchman Review of Arrangements for Coordinating National Security and Intelligence Priorities (the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, July 2013).

52. Office of the Controller and Auditor-General Governance of the National Security System (2016).

53. Michael Wintringham and Jane Jones National Security and Intelligence Framework for New Zealand (2009); Simon Murdoch Report to the State Services Commissioner: Intelligence Agencies Review (2009).

54. Office of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security Report into Government Communications Security Bureau’s process for determining its foreign intelligence activity (2017).

55. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service The NZSIS 10-Year Operational Strategy (Project Sterling) (June 2016).

56. Performance Improvement Framework, footnote 42 above.

57. The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service The 2019 Terrorist Attacks in Christchurch: A review into NZSIS processes and decision-making in the lead up to the 15 March attacks (Arotake Review) (June 2019) at page 20.

58. Simon Murdoch, footnote 10 above at page 26; Jacki Couchman, footnote 51 above.

59. Simon Murdoch New Zealand’s National Security System (April 2011) Section V: Value for Money at page 15.

60. Performance Improvement Framework, at footnote 42 above.

61. Public Finance Act 1989, section 45D.

62. Public Finance Act 1989, section 15A(4)(a).

63. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, footnote 49 above.

64. Allan Gyngell “The Rumble of Think Tanks: National Security and Public Policy Contestability in Australia” in War, Strategy and History: Essays in Honour of Professor Robert O’Neill edited by Daniel Marston and Tamara Leahy (ANU Press, Acton, Australia, 2016) at pages 265–284.