1.1 Overview

1

Earlier in our report we explained how over the last 30 years the diversity of the New Zealand’s population has increased significantly in terms of ethnicity, culture, gender identities, religion, values, languages spoken, ages, sexual orientation and whānau structure (see Part 2: Context). New Zealand has been described as a “superdiverse” country. Superdiversity means “a substantial increase in the diversity of ethnic, minority and immigrant groups in a city or country”.1 One indicator of superdiversity is that a quarter of New Zealand’s population was born overseas.

2

New Zealand is generally regarded as a country with a high level of social cohesion, but underlying vulnerabilities and issues remain that are yet to be fully addressed.2 Sir Peter Gluckman, Director of New Zealand think tank Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Future, told us that “social cohesion is a critical asset for New Zealand and all New Zealand peoples”, suggesting it was something to value, grow and protect and, critically, invest in.

3

Our Terms of Reference directed us to make recommendations about how Public sector systems or operational practices should be improved to ensure the prevention of terrorist attacks in the future.

4

In later chapters of this Part we discuss:

- leadership and oversight in building social cohesion (chapter 2);

- leadership of embracing New Zealand’s increasing diversity (chapter 3);

- hate speech and hate crime (chapter 4); and

- responses to questions asked by the community (chapter 5).

5

In this Part we discuss government social cohesion initiatives and how Public sector agencies have recognised, adapted to and embraced New Zealand’s changing demographics. These issues were not part of our original work plan. As our inquiry progressed and they were raised with us repeatedly by affected whānau, survivors and witnesses, communities and experts, it became clear that these issues have a role to play in Reduction, Readiness and Recovery activities in the counter-terrorism effort and in building the resilience of communities. Our inquiry into the government’s social cohesion initiatives and adaptation to New Zealand’s increasing diversity was not as extensive as that conducted into the counter-terrorism effort (see Part 8: Assessing the counter-terrorism effort). However, it was sufficient to give us an understanding of the issues.

6

While we recognise that diversity has many facets, in this Part we focus on New Zealand’s ethnic and religious diversity because this is of most relevance to our inquiry. New Zealand’s Muslim communities are more ethnically diverse than many people appreciate (for example, affected whānau, survivors and witnesses of the terrorist attack represent around 50 different countries of origin). We do not explore other kinds of diversity in New Zealand such as gender identity, age, sexual orientation and disability.

7

In what follows in this chapter we provide a context for later chapters by explaining:

- social cohesion, social inclusion and community engagement;

- opportunities and challenges associated with New Zealand’s diversity; and

- New Zealand’s response to demographic change.

1.2 Social cohesion

8

There have been many definitions of social cohesion, most of which are associated with wellbeing. We use the definition developed by Professor Paul Spoonley, Robin Peace, Andrew Butcher and Damian O’Neill, which describes a socially cohesive society as one in which all individuals and groups have a sense of:

- belonging – a sense of being part of the community, trust in others and respect for law and human rights;

- inclusion – equity of opportunities and outcomes in work, income, education, health and housing;

- participation – involvement in social and community activities and in political and civic life;

- recognition – valuing diversity and respecting differences; and

- legitimacy – confidence in public institutions.3

9

For Māori, social cohesion means a collective sense of identity and belonging (as Māori) which is respected by broader society as a whole. Sir Mason Durie’s work emphasises the importance of the ability to live as Māori and Māori determining the many facets of what being Māori means.4

10

In New Zealand, social cohesion must be founded on upholding Te Tiriti o Waitangi. It is not about making all New Zealanders the same. It is an inclusive concept that values communities and individuals coming together, where:

- they respect each other and the differences they bring; and

- they develop some shared values, norms and experiences.

11

Social cohesion exists where people feel part of society, family and personal relationships are strong, differences among people are respected and people feel safe and supported by others. Social cohesion is an ideal rather than a goal to be achieved and must continually be nurtured and grown.

12

Social cohesion has broad benefits for society and is an important contributor to long-term prosperity. One commentator suggests that because cohesive societies are politically stable, they can focus on economic growth and business development.5 Other commentators indicate that a cohesive society:

- is mutually supportive of its members, enabling them to pursue common goals by democratic means; and

- develops ways of coping with stresses and divisions in an open democratic manner (for example, disparities of wealth or ethnic or cultural diversity).6

13

Social cohesion can contribute to preventing or countering extremism. This is because cohesive and resilient communities are better placed to resist and counter the risk of radicalisation and mobilisation to violent extremism and terrorism. Tolerant, and ideally inclusive, societies are more able to address and prevent the polarisation and disenfranchisement that can contribute to a rise in extremism. However, social cohesion should be pursued separately from New Zealand’s counter-terrorism efforts as it is important in itself and has wider social, economic and cultural objectives. As well, undertaking social cohesion activities as a tool to counter extremism may have the effect of stigmatising and alienating some members of communities, thereby undermining the aims of social cohesion work.

1.3 Social inclusion

14

Social inclusion is the process of improving how individuals and groups participate in and contribute to society on their own terms.

15

For New Zealand it is important to acknowledge that Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the evolving Māori-Crown relationship must underpin any social inclusion processes. That is, any such processes must be based on New Zealand’s bicultural foundations while welcoming and supporting our increasingly vibrant and diverse population as an ongoing strength.

1.4 Community engagement

16

Community is a word used to convey notions of social relationships, cultural values and belonging or having something in common. We use the term community in this report broadly to include groups of people that may come together, for example, in terms of locality, religion, ethnicity, occupation, special interest or online.

17

Community engagement is the process of working with a community or communities to address issues affecting their wellbeing. The process of community engagement is focused on building enduring, trusted relationships. According to the International Association for Public Participation, “community engagement … is now accepted as a standard component of any significant project as much as traditional disciplines as planning, development and implementation”.7

18

Public sector agencies in New Zealand use feedback received through community engagement to inform policy development, service design and decision-making. We use the term community engagement, rather than “public consultation”. We are aware that many laws provide for public consultation as determined by the particular legislative regime and case law. For example, the Public Service Act 2020 imposes an obligation on a chief executive to undertake public consultation on a long-term insights briefing (information and analysis on medium and long-term trends, risks and opportunities that may affect New Zealand society) and take any feedback received into account when finalising the briefing.8 Consultation is only one form of community engagement, see below.

19

In 2013, New Zealand signed up to the Open Government Partnership. That Partnership is about strengthening democracy in New Zealand by ensuring that citizens can contribute and influence what government does and how it does it. As part of that Partnership, New Zealand committed to “develop a deeper and more consistent understanding within the New Zealand public sector of what good engagement with the public means”.9

20

The International Association for Public Participation sets out good practice for engagement. It includes a set of core values, suggesting that public participation should:

- be based on the belief that those who are affected by a decision have a right to be involved in the decision-making process;

- include the promise that the public’s contribution will influence the decision;

- promote sustainable decisions by recognising and communicating the needs and interests of all participants, including decision-makers;

- seek out and facilitate the involvement of those potentially affected by, or interested in, a decision;

- seek input from participants in designing how they participate;

- provide participants with the information they need to participate in a meaningful way; and

- communicate to participants how their input affected the decision.10

21

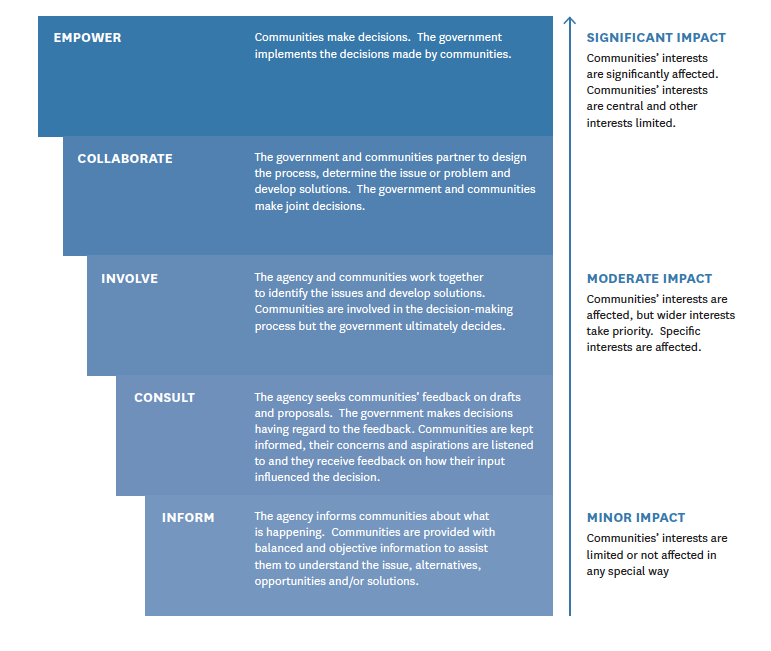

The purpose of these core values is to “help make better decisions which reflect the interests and concerns of potentially affected people and entities”. We set out the different types of engagement below, drawing on the IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum11 but with some additional information and adaptation to make them more relevant to New Zealand:

Figure 48: Levels of community engagement

22

The International Association for Public Participation also sets out a quality assurance process12 for community and stakeholder engagement that involves a number of steps outlined in the figure below.

Table 14: Quality assurance process for community and stakeholder engagement

Step |

Actions |

|

Problem definition |

Clearly defining the purpose of the engagement and why the planned engagement is occurring. This requires clear objectives and rationale for the engagement, identifying the issues to be addressed, the communities affected, the ideal outcome the decision-makers have identified and who decides when a resolution has been achieved. |

|

Agreement of purpose or context and identification of negotiables and non-negotiables |

Clearly articulating the context and objectives of engagement, where there are opportunities for community influence and input and the non-negotiable elements of decision-making. |

|

Level of participation |

Determining the level of influence will be apparent based on the goals of engagement. Various degrees of participation are appropriate and legitimate depending on the context and purpose of the decisions being made. |

|

Stakeholder identification and relationship development |

Identifying those who are directly involved or affected, are likely to be affected or impact the project outcome and those who need a voice. Once identified, it is necessary to understand the interests, values and needs of each stakeholder group, including expectations and potential points of conflict. This step will inform the communication and engagement techniques appropriate to the project. |

|

Project requirements |

Considering the specific requirements of the project that will influence the methodology used in engagement. Requirements include timeliness, statutory and policy requirements, reporting and resource constraints |

|

Development and approval of engagement plan |

Clearly setting out the way stakeholder groups will be involved in influencing the project. The engagement plan will set out matters such as the purpose and objective of engagement, engagement activities, resources required, a risk management plan, roles and responsibilities of the project team, reporting mechanisms and evaluation points. |

|

Execution of engagement plan |

Engagement should be undertaken as set out in the engagement plan. |

|

Feedback |

Providing information to stakeholders about how engagement outcomes will inform decision-making. Feedback needs to be collated and made available to all stakeholders involved in the engagement. |

|

Evaluation and review |

Reviewing engagement to determine whether it has met the identified requirements, achieved the objectives and whether further engagement is required. |

|

Monitoring |

Ongoing monitoring and review at regular intervals is necessary to ensure engagement is effective and should be used to influence continuous improvement of engagement practices. |

|

Documentation of evidence |

Documentation relating to the steps set out above is important for auditing, to ensure engagement processes can be assessed for quality assurance. |

1.5 Opportunities and challenges associated with New Zealand’s diversity

23

New Zealand’s population is growing more diverse and is projected to become even more so in the next 20 years (see Part 2: Context). New Zealand’s increasing diversity brings both opportunities and challenges for communities. Professor Paul Spoonley says that a substantial increase in the scale and scope of ethnic groups in a region can provide certain economic benefits, such as:

- higher productivity and innovation for regions and cities with large immigrant populations;

- an environment for the cross-fertilisation of ideas that contributes to creativity and innovation;

- investments and increased local aggregate demand created by diversity encouraging product and process innovation; and

- reflecting and contributing to new global connections and a local or international cosmopolitanism.

24

However, there are challenges:

- Superdiversity challenges the assumptions and practices of a shared civic culture and citizenship, and raises concerns about social cohesion.

- Anxieties about the growing diversity of labour markets and communities have been associated with discrimination and anti-immigrant politics.

25

Professor Paul Spoonley suggests that public policy is critical in addressing these points in order to realise the benefits of diverse populations through “support for intercultural dialogue, adopting anti-discrimination laws, improving credentials recognition, promoting language training and job search techniques and ameliorating disadvantage that impedes social mobility”.13

26

Similarly, the Superdiversity Centre for Law, Policy and Business published a report in 2015 on the impact of increased diversity on business, the government and New Zealand noting that:

- the government needs to move faster on diversity – government is responding more slowly to New Zealand’s superdiversity than business;

- even when superdiversity is considered, it is sometimes an afterthought, tacked on to mainstream policies and campaigns with minimal budgets attached;

- many of the challenges posed by ethnic diversity are not new, such as discrimination against ethnic minorities;

- the transition to superdiversity represents a much larger and permanent change in New Zealand’s demographic make-up compared to those of most Western countries; and

- the challenges faced by migrants when interacting with Public sector agencies and the law are unique, and laws and policies need to take that into account.14

27

Public sector agencies, local government, civil society and community groups all play a role in finding ways to bring people together to build trust and confidence between communities and institutions.15

1.6 New Zealand’s response to demographic change

28

There are different views on how well New Zealand is responding to its demographic change. Stats NZ’s Wellbeing statistics: 2018 showed that nearly 90 percent of those New Zealanders who responded to the General Social Survey felt comfortable or very comfortable about a new neighbour who was a different ethnicity or religion to themselves.16

29

On the other hand, there is evidence that some communities in New Zealand experience attitudes or harmful behaviours that make them feel less included or valued.

30

In 2012 the Human Rights Commission revealed that structural and institutional racism and discrimination existed in New Zealand across health, education, employment, income and justice outcomes, and in the Public service. Common elements found across these outcomes were:

- entrenched ethnic inequalities (for example, in health and educational outcomes);

- the cumulative effect of discrimination, as discrimination at one stage or one system can flow on to other stages and systems (for example, barriers in early childhood education contribute to poor educational outcomes at higher levels);

- biased practice by practitioners, including doctors, teachers, New Zealand Police, judges and Public sector employees;

- an assumption that everyone has equal access to services, which ignores the barriers that some members of society experience; and

- insufficient or poor quality data collection on ethnicity.17

31

There is clear evidence that many communities, including ethnic and religious communities, are socially excluded in New Zealand. A 2020 report by the Ministry of Social Development confirmed that:

… there is consistent evidence of:

- persistent and marked disparities in New Zealanders’ attitudes towards selected social groups. Data captured annually through the New Zealand Attitudes and Values survey, for example, shows that New Zealanders overall consistently rate European New Zealanders more favourably than a range of other social groups

- Data from Stats NZ’s 2016 General Social Survey shows that approximately 17 per cent of all New Zealanders report having experienced discrimination in the last 12 months. Compared to this overall rate, the rates are markedly higher for younger people (e.g. 24% of 15–24 year olds), women (19.3%), the unemployed (27.3%), people who do not own their own home (21.8%), single parents (26.9%), recent migrants (25.8%), non-Europeans (e.g. 22.7% of Māori and 24.3% of Asians) and people with a disability (21.9%).

- On balance, the evidence points to a very mixed picture about the extent of social inclusion within New Zealand. Although a majority of New Zealanders claim to be accepting of diversity, there are still substantial numbers of New Zealanders who are left behind and marginalised because of discrimination and prejudice. Some commentators also note not only a lack of awareness but also a reluctance to acknowledge the extent of the problem.18

32

Attitudes or harmful behaviours that reduce social cohesion and inclusion have particular impact for Muslim communities. The 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States of America by Islamist extremists have given Muslim communities unwelcome visibility in many Western democracies. Muslim communities have become subjected to both the attention of intelligence and security and law enforcement agencies and negative comments and harassment from members of the wider community.

33

For Muslim communities in New Zealand, this has led to a perception that they are persistently placed in a one-dimensional frame by both wider society and the Public sector agencies that are responsible for the support and protection of all New Zealanders. That frame has been referred to as “securitisation” by those who made submissions to us. Securitisation means that, as a group, Muslim individuals and communities are primarily seen as a potential threat to New Zealand’s national security.

34

A study in the United Kingdom about the portrayal of Muslim communities in the media and the impact of that coverage observed that:

The evidence shows an overwhelmingly negative picture, where threat, otherness, fear and danger posed or caused by Muslims and Islam underpins a considerable majority of the media’s coverage. Given that 64% of the British public claimed that what they know about Muslims and Islam is acquired through the media, then it could be that such a stream of negativity …. has the potential to then ensure stigmatisation, marginalisation and intolerance.19

35

The role of the media in perpetuating stereotypes has been recognised at the international level:

The media often perpetuates … stereotypes by disseminating or providing a platform for racists and xenophobic speech. The Special Rapporteur would also like to highlight that media bias is a particularly problematic phenomenon in a counterterrorism context. The disproportionate coverage of certain types of terrorism, the use of certain terminology or images and the overall framing of news stories about terrorism distorts public perception. A recent study examined the domestic media coverage of terrorist attacks that occurred in one North American country during the period 2011–2015. The study found that attacks by Muslim perpetrators, particularly foreign-born Muslims, received 4.5 times more coverage than other attacks. Only a small proportion of attacks were perpetrated by Muslims (12.4 per cent) or foreign-born Muslims (5 per cent). Yet, these attacks received 44 per cent and 32 per cent of the news coverage, respectively. Research also found that an attack is more likely to be considered an act of terrorism when carried out by a Muslim. By contrast, threats posed by right-wing violence are often underestimated and not considered to be terrorism.20

36

A 2020 Comparative study of attitudes to religious groups in New Zealand found that:

One plausible explanation for the patterns revealed in our results is media effect: prejudice arises from the perceived threat of Muslim radicals. Indeed, Shaver et al. (2017) found that greater media exposure predicted greater anti-Muslim prejudice.

…

The importance of the media’s role in strengthening or weakening prejudice is likely exacerbated by a general lack of knowledge and education on different religions, and a lack of contact between most New Zealanders and diverse religious groups: Muslims comprise only 1.3% of the population and Buddhists 1.1% ([Stats NZ] 2019). This means that for many New Zealanders the media provides their only exposure to religious diversity.21

37

The study also found:

… substantially greater perceived threat and negativity towards Muslims compared with other groups. In particular, older people, New Zealand Europeans, men, and those with more right-wing attitudes report greater threat and negativity towards Muslims. In line with previous studies, higher religious identification and higher education predict greater acceptance. Taken collectively, these results reveal that the Muslim Acceptance Gap in this country is substantial, and greater challenges for acceptance are evident among lower-educated, right-wing, older, secular, and male populations. The magnitude of this gap reveals a substantial challenge to the future of New Zealand where religious and secular people can live without evoking prejudice.

38

Another 2020 article Prejudice toward Muslims in New Zealand: Insights from the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study by Chris G Sibley and others noted that New Zealanders have felt “less warmth” towards Muslim communities than other groups in New Zealand every year since the New Zealand Attitudes and Values survey started in 2012.22

1.7 Concluding comments

39

It is not possible or desirable to expect everyone in society to think and behave in the same way. That sort of uniformity is not what we mean when we talk about social cohesion. Nor do we mean that marginalised communities should conform to majority cultural values and practices – in other words, to assimilate. Instead we see social cohesion as enabling everyone to belong, participate and have confidence in public institutions. This requires recognition and respect of diversity and valuing differences leading to equitable opportunities and outcomes in work, income, education, health, housing etc. Inclusion is a measure of how a society enables that diversity to thrive.

40

In the Public sector, we observe that social cohesion has (incorrectly) come to be perceived as implying social uniformity achieved through assimilation. For this reason Public sector agency documents have recently used the narrower term social inclusion rather than the broader term social cohesion.

41

In chapter 2 we look at leadership and oversight of social cohesion at the political and Public sector agency level. In chapter 3 we focus on Public sector efforts to embrace New Zealand’s increasing diversity, which we see as an important component of enhancing social cohesion. This is primarily through workforce capacity and capability and how the Public sector is structured to respond to New Zealand’s diverse populations. In chapter 4 we address hate speech and hate crime, which are the unacceptable consequences of non-inclusive and non-cohesive aspects of our society and unwillingness by some to embrace diversity.

42

A series of themes have emerged as a result of our inquiries, which we explore through the rest of this Part:

- There has been limited political leadership and public discussion of social cohesion, inclusion and embracing diversity.

- There has been no overarching strategy and little strategic analysis.

- Public sector leadership and coordination have been diffuse.

- Community engagement processes have been limited and poor.

- Public sector support for community capacity development has been ad hoc.

- Data collection and analysis and monitoring and evaluation are under-developed.

- Public sector workforce capacity and capability to embrace diversity are far from complete.

----------

1. Paul Spoonley Superdiversity, Social Cohesion, and Economic Benefits (IZA World of Labour, May 2014) at page 1.

2. Paul Spoonley, Peter Gluckman, Anne Bardsley, Tracey McIntosh, Rangimarie Hunia, Sarb Johal and Richie Poulton He Oranga Hou: Social cohesion in a post-COVID world (Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures, The University of Auckland, May 2020) https://informedfutures.org/wp-content/uploads/Social-Cohesion-in-a-Post-Covid-World.pdf.

3. Paul Spoonley, Robin Peace, Andrew Butcher and Damian O’Neill “Social Cohesion: A Policy and Indicator Framework for Assessing Immigrant and Host Outcomes” (April 2005) 24 Social Policy Journal of New Zealand at pages 98–99.

4. Mason Durie “Measuring Māori Wellbeing” (2006) New Zealand Treasury Guest Lecture Series https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2007-09/tgls-durie.pdf.

5. Jo Ritzen and Michael Woolcock “Social Cohesion, Public Policy, and Economic Growth: Implications for Countries in Transition” (Paris, 26-28 June 2000) Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics.

6. Ministry of Social Development Social Inclusion in New Zealand – Rapid Evidence Review (May 2020) https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/social-inclusion-in-new-zealand-a-rapid-evidence-review/index.html.

7. International Association for Public Participation Australasia Quality assurance standard for community and stakeholder engagement (2015) https://iap2.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/IAP2_Quality_Assurance_Standard_2015.pdf.

8. Public Service Act 2020, Schedule 6, clause 9.

9. Open Government Partnership New Zealand National Action Plan 2018-2020 (2018).

10. International Association for Public Participation IAP2 Core Values for Public Participation (2020).

11. International Association for Public Participation IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum (2020).

12. International Association for Public Participation Australasia, footnote 7 above at pages 16–25.

13. Paul Spoonley, footnote 1 above.

14. Mai Chen Superdiversity Stocktake: Implications for Business, Government and New Zealand (Superdiversity Centre for Law, Policy and Business, Auckland, 2015)

15. Michele Grossman, Mario Peucker, Debra Smith and Hass Dellal Ao Stocktake Research Project: A systemic literature and selected program review on social cohesion, community resilience and violent extremism 2011-2015 (Victoria University and Australian Multicultural Foundation, 2016); Shandon Harris-Hogan, Kate Barrelle and Andrew Zammi “What is countering violent extremism? Exploring CVE policy and practice in Australia” (2016) 8(1) Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression at page 6; Peter Romaniuk Does CVE Work? Lessons Learned From the Global Effort to Counter Violent Extremism (Global Center on Cooperative Security, 2015); Canada Centre for Community Engagement and Prevention of Violence National Strategy on Countering Radicalisation to Violence (2018).

16. Stats NZ Wellbeing statistics: 2018 (2018) https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/wellbeing-statistics-2018.

17. New Zealand Human Rights Commission A fair go for all? Rite tahi tātou katoa? Addressing Structural Discrimination in Public Services (2012).

18. Ministry of Social Development, footnote 6 above at page 18.

19. Dr Chris Allen Written evidence to the All Party Parliamentary Group on Islamophobia post-Woolwich 2013 (15 July 2013), cited in Elizabeth Arif-Fear Muslims in the Media: Are we bridging or building divides? (20 May 2019) https://faithbeliefforum.org/muslims-in-the-media-are-we-bridging-or-building-divides/.

20. United Nations Report of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance (2017) A/72/287 https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1304009?ln=en.

21. Lara M Greaves, Aarif Rasheed, Stephanie D’Souza, Nichola Shackleton, Luke D Oldfield, Chris G Sibley, Barry Milne and Joseph Bulbulia “Comparative study of attitudes to religious groups in New Zealand reveals Muslim-specific prejudice” (2020) 15(2) Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online.

22. Chris G Sibley, M Usman Afzali, Nicole Satherley, Anastasia Ejova, Samantha Stronge, Kumar Yogeeswaran, Michael Grimshaw, Diala Hawi, Zahra Mirnajafi, Fiona Kate Barlow, Petar Milojev, Lara M Greaves, Sarah Kapeli, Elena Zubielevitch, Logan Hamley, Maria C Basabas, Marvin H Wu, Chloe Howard, Carol HJ Lee, Yanshu Huang, Christopher Lockhart, Joaquín Bahamondes, Sam Manuela, Taciano L Milfont, Ryan Perry, Nikhil K Sengupta, Nickola C Overall, John H Shaver, Geoffrey Troughton, Danny Osborne and Joseph Bulbulia Prejudice toward Muslims in New Zealand: Insights from the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study (July 2020).