Distressing content:

This section of the report contains material that may be confronting, particularly to those affected by the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack.

5.1 Introduction

1

It is not possible to understand the pattern of events that both led to, and demonstrated, the individual’s radicalisation without a general understanding of extreme right-wing thinking and some of its markers.

2

A description of the key dynamics of right-wing extremism is also required to understand the harms that communities have told us they have experienced.

3

The discussion that follows outlines what we mean by extremism and why it is important to look at a spectrum of behaviours and their consequences for society. We then address aspects of extreme right-wing thinking and behaviour that are relevant to the account we are about to tell about the individual, the behaviours evident in his radicalisation and mobilisation to violence and his resort to terrorism (see Part 4: The terrorist). Not wishing to amplify extreme right-wing ideologies, we do not provide a complete survey. We also discuss what we mean by radicalisation to violence and outline some of the drivers of radicalisation, and the challenges for Public sector agencies in identifying and mitigating the threat from right-wing extremism.

5.2 Extremism

4

Extremism is generally understood as a belief system underpinned by rigid and uncompromising beliefs outside the norm of a society. In the case of New Zealand this might be by rejecting democracy, the rule of law and human rights.64 Extremism can have different ideological underpinnings and manifest in a number of ways. Central to extremist belief systems is a desire to bring about change and overhaul the political, social or religious environment to conform to the person’s or group’s idealised vision of society.

5

Extremist belief systems are characterised by a strong “us versus them” mentality, and belief in the supremacy of, or at least strong loyalty to, the group a person is part of.65 This can be any political, religious, social, ethnic or other grouping. Anyone outside of that group (for example, people from a different religion or ethnicity) can present a threat to the group’s existence. The group’s survival is therefore contingent on hostility towards and suppression of those who are outside the group.66

A spectrum of behaviours

6

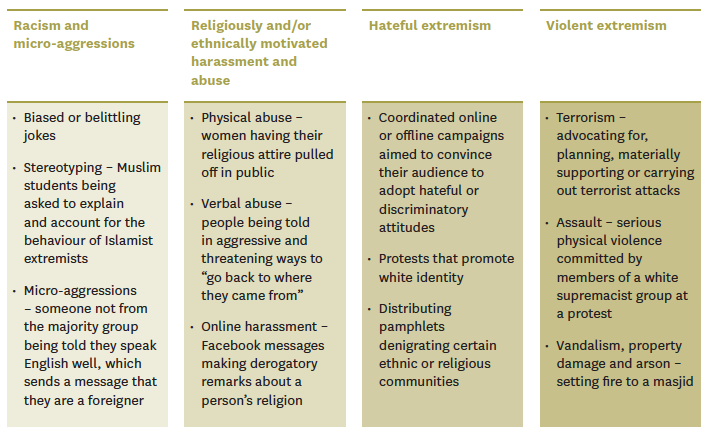

In this report we will talk about a range of behaviours that cause harm to people, some of which are inspired by extremist ideologies and others which are not. These do not represent all the types of behaviours that cause harm but are those that are most material to our inquiry.

7

Having extreme beliefs does not automatically lead to violence and the majority of those who subscribe to an extremist ideology do not commit acts of violence. Violent extremism only occurs where an individual or group believes that violence is a legitimate (and often the only) way through which they can achieve systemic change. Violent extremism encompasses any violent actions committed to further extremist aims, including vandalism, spontaneous violence and terrorism.67

8

International evidence has shown there are also behaviours underpinned by an extremist ideology that are not violent but nonetheless can cause harm to individuals and create fear and division within societies.68 This occurs when they are done with the intention of inciting or amplifying hate against a group. The United Kingdom Commission for Countering Extremism uses the term “hateful extremism” to describe “behaviours that are actively hateful or incite hate towards an identified out-group for the survival of an in-group”.69 This includes conduct that spurs hatred, such as protests or campaigns led by extremist groups that involve denigrating, insulting, belittling or vilifying perceived others. Some activities conducted by individuals and groups in what we term the radical right below would fit within this category.

9

There are also a wide range of behaviours that are targeted at people based on their ethnicity or religion.70 These behaviours are not what would be termed extremist (as they are not motivated by a desire for change) but are underpinned by hostile attitudes to people of certain religions and ethnicities. This can include physical and verbal harassment.

10

Other behaviours that can cause harm are racist remarks or micro-aggressions. Racist remarks and micro-aggressions are similar and have been defined as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory or negative slights and insults”.71 This includes, for example, making statements that reinforce negative stereotypes about ethnic or religious communities or making statements that cause people who are not from the majority group to feel that they do not belong.

Figure 5: Spectrum of harmful behaviours

11

While extremist views may be seen by wider society as morally abhorrent or problematic, holding such views and acting on them in certain ways (for example through public engagement and protest) is often not illegal.72 Describing behaviours that do not involve violence or the threat of violence as extremist and seeking to discourage or impose legal or social sanctions on them have presented challenges (for instance, complaints that rights to freedom of speech and democratic debate are being limited) and, in this way, exacerbated polarisation.73

12

We are also interested in behaviours further along the spectrum and which sit outside the counter-terrorism effort. This is because there are often “fluid boundaries” between hate crime and terrorism especially in the case of right-wing extremism.74 Internationally we have seen that violence sits at the peak beneath which are many other behaviours that cause harm and create an environment that is conducive to violence.75

13

Many individuals and groups who engage in behaviours that could be considered hateful extremism support dehumanising and divisive rhetoric against perceived others but are careful to avoid direct engagement with, or endorsement of, violence.76 Rhetoric of this kind can shift the boundaries of what is considered acceptable public debate towards a normalisation of, for example, Islamophobic and anti-immigrant sentiment.77 It is likely that these behaviours encourage and legitimise the use of violence.78 We discuss this in regards to the far right below.

14

Behaviours outside of violent extremism can cause harm at the individual level to the mental health and wellbeing of those who are targeted, and at the societal level through increased social division, intolerance and polarisation.79 This can have negative impacts on social cohesion. We discuss this in more detail in Part 9: Social cohesion and embracing diversity.

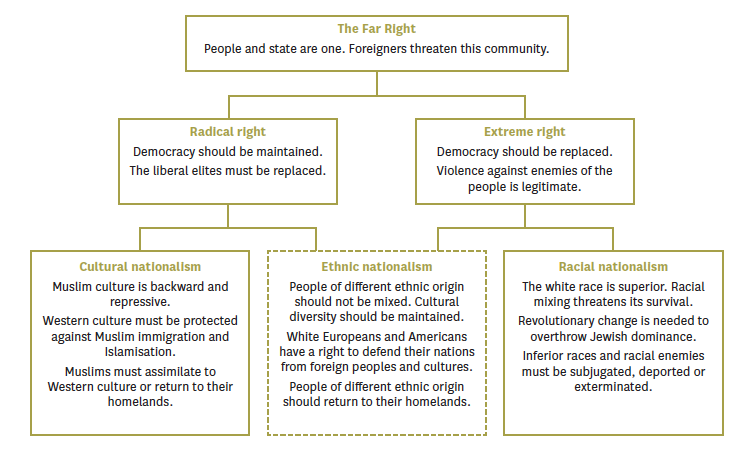

5.3 The nationalist far right, the radical right and the extreme right-wing

15

To the right of traditional right-wing conservative and libertarian opinions is a political space that has been called the far right. It is occupied by a range of ideologies, orientations and patterns of thinking. These include a strong form of nationalism that is not so much an ideology80 but rather an orientation that holds that western civilisation and its values are under threat from non-native (or alien) elements, whether people (particularly immigrants) or ideas (such as multiculturalism). It is this form of far right thinking that is primarily relevant for our inquiry. There are other far right patterns of thinking – including “deep-state” conspiracy theories (such as QAnon)81 or anti-feminist ideologies (such as “incel” ideology).82 While sexist attitudes often form part of extreme right-wing thinking and anti-feminist ideologies can act as a gateway to other extreme right-wing ideologies,83 these patterns of thinking are of less relevance for our purposes. Right-wing extremism experts Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal have provided a simple taxonomy of the nationalist far right, which for the purposes of this report, we adopt.84

Figure 6: Taxonomy of the nationalist far right

16

What Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal define as the radical right is encompassed by the broad concept of extremism that we outlined earlier. While involving a slightly different usage of extremism, the distinctions drawn by Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal have considerable explanatory value in the context of right-wing thinking and action.

17

Within the Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal taxonomy, the radical right works for change within the framework of democracy (for example, through changes to immigration policy), whereas extremists are willing to use, or more commonly express support for, non-democratic methods such as violence to achieve their political aims.85 There are radical right political parties in Western countries that participate in elections.

18

There is considerable overlap in the underlying thinking of those on the radical right and extreme right-wing. For legal and tactical reasons, those on the extreme right-wing tend to avoid public statements advocating violence and thus are not always easy to distinguish from those on the radical right. There has been a concerted effort by some extreme right-wing groups to tone down extreme discourse in order to reach and engage with a larger number of individuals. These groups may use less extreme figureheads and channels to reach new audiences and in this way shift the boundaries of what is “acceptable public discourse”.86 Further, given the implausibility of the expressed aims of some of those on the radical right, most particularly peaceful implementation of lawfully imposed requirements for Muslim individuals to return to their homelands (referred to sometimes as “remigration”), it is questionable whether associated rhetoric should be taken at face value.

19

Another complication, particularly for counter-terrorism agencies, is that of those who advocate for or express support the use of violence and are thus on the extreme right-wing of Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal’s taxonomy, most are “talkers” and very few are actually committed to following through on, or materially supporting, extremist violence or terrorism.

20

There are three classes of nationalism identified by Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, although these are not mutually exclusive:

- Cultural nationalists87 promote a version of nationalism in which the nation is defined primarily in terms of culture and history.88 They tend to reject the idea that some races are superior to others and focus on what they perceive as cultural differences, for example claiming that beliefs associated with Islam are incompatible with Western culture and democracy.89 Gaining in popularity after the attacks of 11 September 2001 (and more recently the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe), these movements tend to present themselves as opposed to Islamist extremism rather than Muslim communities.90 While cultural nationalists have grievances against a variety of groups, their primary grievance is against Muslim immigrants. Many cultural nationalists claim there is a conspiracy to “Islamise” Europe through the “stealthy” imposition of Islamic Sharia law. Almost all Muslim individuals and communities in the West are seen through this frame, with evidence of “Islamisation” seen everywhere – even in the availability of halal meat in the West.91 The radical right call for the protection of Western or European culture through policies such as banning the building of masajid in Western countries and stopping all Muslim immigration.92

- Ethno-nationalists/ethnic nationalists tend to emphasise differences between ethnic groups (based on cultural and linguistic differences), rather than promoting racial hierarchies.93 They believe that all ethnic groups, including Europeans, have a right to protect their unique culture and identity. Ethnic mixing is seen to be harmful and they often have grievances against a wide range of groups.94 Examples of this type of ideology are the Identitarian95 movements in Europe and the more moderate wing of the “Alt-Right” (sometimes referred to as the “Alt-Lite or Alt-Light”) in the United States of America. Self-identifying ethno-nationalists generally do not encourage or support violence in public, although are often found either explicitly or implicitly supporting violence within closed groups.

- Racial nationalists define the ideal nation in racial terms, embracing the idea of an original state of society that existed before the ethnic make-up was altered (by waves of immigration).96 They fight for a society based on racial purity and the separation of races, drawing inspiration from National Socialism (Nazism), Fascism and varieties of white supremacy. Racial nationalists often embrace anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that Jews promote immigration, equality and racial mixing to destroy the “white race”. Cultural nationalists and ethno-nationalists also often subscribe to these same anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. They tend to reject the values of democracy and human rights and consider violence a legitimate means to achieve their goals (though not always).97

21

Common to much far right thinking is “the Great Replacement” theory, popularised by the French author Renaud Camus in 2011 (though drawing on a tradition going back to the 19th century).98 This theory is that native inhabitants of Western or European countries are being replaced by non-European peoples through immigration and the growth of ethnic minority communities. Soon, immigration and declining white birth rates will result in the native (white) population becoming a minority. Muslim immigrants are typically singled out as a threat.99 This theory is closely linked to conspiracy theories popular among ethno-nationalists and racial nationalists (including white supremacists), including the ideas of “white genocide”,100 “Eurabia”101 and “cultural Marxism”.102

22

As we will explain, the individual’s political thinking was far right in nature and showed many of the signs of ethno-nationalism (see Part 4: The terrorist).

Race war and accelerationism

23

Some on the extreme right-wing see race war – a large-scale clash between races pitting whites against all others – as inevitable, desirable or both. They sometimes allude to this using other terms, including “Rahowa” (a contraction of Racial Holy War) and “Day of the Rope”.103 “Accelerationists” advocate and commit acts of violence on the basis that they are likely to set off a chain of events involving action and reaction that will bring forward the race war and the hoped-for consequence of a white ethno-nationalist state.

Use of the internet

24

One of the most notable changes in the right-wing extremist movement has been its movement from the streets to the internet. In previous decades, the extreme right-wing mostly organised on the streets in gangs or protest movements. Today, extremism has substantially, although not completely, moved from physical meetings and street activism to the internet and social media.104

25

Right-wing extremists were some of the earliest to use the internet for extremist purposes.105 For example, the world’s largest white supremacist website, Stormfront, was established in 1996.106 More recently, the extreme right-wing has exploited the power of the internet through an array of online platforms and spaces, which it uses to connect with like-minded people and ultimately to recruit new members, some of whom have committed acts of violence and terrorism.107 Indeed, lone actor right-wing extremist terrorists, such as the individual, are never quite alone as they are often part of virtual communities on the internet.108

26

People from different ideological viewpoints (Identitarians, neo-Nazis and incels) are converging on similar platforms.109 Research suggests that these platforms are instrumental in spreading right-wing ideology across different online communities, including more mainstream ones.110 The European anti-Islamic vigilante group, Soldiers of Odin, has used Facebook as a propaganda and recruitment tool to spread anti-Muslim hate globally. Researchers estimated that the Pan-European white nativist group known as Generation Identity had – as of May 2019 – approximately 70,000 followers on its official Twitter account.111 The main accounts of these groups have subsequently been banned from Twitter and Facebook, although groups such as these often use unbranded pages to avoid these bans.

27

As extremist content is increasingly removed from the major platforms, right-wing extremists are gathering more and more on unmoderated fringe platforms. The platform Gab (a hybrid of Twitter and Facebook) was established in 2016 in direct response to the removal of prominent far right and right-wing extremist figures from major social media platforms. The site has been widely described as a “safe haven” for right-wing extremists. By the end of 2018 it had approximately 450,000 users and had posted approximately 30 million comments.112 It sees “populist political candidates, Identitarians, neo-Nazis and alt-right trolls mingle, allowing for the transfer of ideas which leads to a more cohesive ideology”.113 Gab came to public attention when it emerged that the man who killed 11 people at a Pittsburgh synagogue in October 2018 had been an active user.114

28

Other platforms that were not set up for hosting right-wing extremist content – including Reddit and 4chan and some online gaming platforms – have been “hijacked” by right-wing extremists. After the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack, a popular Reddit pro-President Trump forum (or “subreddit”), “The_Donald” contained posts justifying the attack and promoting anti-Muslim hate,115 although it has subsequently been removed by Reddit.

29

4chan started by providing forums for subcultures of young people and Japanese manga and anime enthusiasts.116 Over the years, these forums expanded to include a wider range of topics contained on image boards. These boards are entirely anonymous, with no user details or logins required. 4chan’s “politically incorrect” board is infamous for being dominated by extreme right-wing content. 8chan was basically “a more extreme version of 4chan” and “was known as being a haven for [right-wing extremist] causes almost from its founding”.117 In 2019 it was associated with four deadly terrorist attacks – the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack, a synagogue attack in Poway, California on 27 April 2019, a Walmart attack in El Paso, Texas on 3 August 2019 and a mosque attack in Bærum, Norway on 10 August 2019. These terrorist attacks were all perpetrated by individuals who were active on 8chan. Each attacker pre-announced their intentions, and two of them uploading their manifestos, on the platform’s forums.118

30

In the past, YouTube has been often associated with far right content and radicalisation. There has been much debate about the way YouTube’s recommendation system works.119 One theory is that this system drove users to ever more extreme material into what is sometimes said to be a “rabbit-hole”. An alternative theory is that the way in which YouTube operates facilitates and has monetised the production of videos that attract viewers and the widespread availability of videos supporting far right ideas reflects the demand for such videos.120 What is clear, however, is that videos supporting far right ideas have been very common on YouTube. YouTube has made changes in response to these criticisms, in particular to their recommendation system, so it is less likely to continue recommending increasingly extreme content and has also made it more difficult to access extreme content.

Propaganda, “humour”, irony and lulz

31

In December 2017, the style guide for the far right website, the Daily Stormer, was leaked. It provides insight into the established conventional strategies and tactics used within extreme right groupings. A common tactic is to draw people in with a particular type of humour. Two passages are of interest:

It should be understood first and foremost that the Daily Stormer is not a “movement site”. It is an outreach site, designed to spread the message of nationalism and anti-Semitism to the masses.

This has worked out very well so far, and the site continues to grow month by month, indicating that there is no ceiling on this. As such, though we do mean to keep readers who are already in the know informed and entertained, it should always be considered that the target audience is people who are just becoming aware of this type of thinking.

The goal is to continually repeat the same points, over and over and over and over again. The reader is at first drawn in by curiosity or the naughty humor and is slowly awakened to reality by repeatedly reading the same points. We are able to keep these points fresh by applying them to current events.

…

Lulz

The tone of the site should be light. Most people are not comfortable with material that comes across as vitriolic, raging, non-ironic hatred.

The unindoctrinated should not be able to tell if we are joking or not. There should also be a conscious awareness of mocking stereotypes of hateful racists. I usually think of this as self-deprecating humor – I am a racist making fun of stereotype of racists, because I don’t take myself super-seriously.

This is obviously a ploy and I do want to gas kikes. But that’s neither here nor there.

Right-wing extremism in New Zealand

32

Although the individual was an Australian citizen we do not describe the extreme right-wing in Australia. This is because we are not investigating the actions of Australian Public sector agencies. We briefly explain below what is known about the radical and extreme right-wing in New Zealand. This is not because the individual had any known connections with New Zealand individuals or groups. We later assess the activities of Public sector agencies in relation to right-wing extremism and the following description provides an explanation of what is currently known about right-wing extremism in New Zealand (see Part 8: Assessing the counter-terrorism effort).

33

Right-wing groups have been active in New Zealand for many decades and there have been at least three hate crime murders (committed by members of the Fourth Reich, a right-wing gang). Right-wing extremism in New Zealand has followed a similar trajectory to that seen internationally. Street-based neo-fascist and white power groups that were prominent up until the early 2000s have given way to new configurations of online groupings connected to an international alt-right movement.121

34

Jarrod Gilbert and Ben Elley who study the alt-right in New Zealand have speculated that similar conditions exist here as have given rise to new alt-right groups elsewhere, such as the ongoing effects of the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis, growing income inequality and a shrinking middle-class.

35

A small number of alt-right groups in New Zealand have emerged, including those targeting universities for recruitment. These groups appear to share similar ideological roots to groups on the far right in the United States of America and elsewhere. For example, one such group describes themselves as an “identitarian activist organisation committed to the revitalisation of our country and our people”, and opposed to immigration (amongst other things). These groups have avoided making overtly racist statements and use terminology “commonly employed by the alt-right to signal white nationalism while maintaining plausible deniability”.122

5.4 Radicalisation to violence

36

Most people with extreme right-wing views do not act on these views through violence. The process through which people develop commitment to a particular extremist ideology is called radicalisation. The process through which an individual comes to see violence as a feasible tool to address their grievances is called radicalisation to violence.

37

Radicalisation to violence is highly individualised and there is not one model that can explain why people choose to commit violence. Rather, a person’s individual characteristics (their background, life experiences and personality), the social groupings they are part of and the wider socio-economic and political environment they live in, all interact in unique ways influence a person’s likelihood of radicalising.123

38

Certain social, political and economic conditions can create environments that are more conducive to the development of extremist worldviews and behaviours. They may lead individuals to feel aggrieved and perceive violence as a legitimate way to act on their grievances.124 For example, the Global Financial Crisis caused economic insecurity and downward social mobility for many people. This created conditions in which some felt that their status and the material advantages they were owed were under threat, leading to a sense of grievance, frustration and a heightened (and regressive) commitment to protecting Western norms and values.125

39

The conditions a person grew up in can play a role in their radicalisation, although precisely how will vary. Some people will progressively develop extremist views over their lifetime and others will be triggered by specific incidents or events.126 While there is no common socio-economic profile, a number of studies have shown those who are susceptible to right-wing extremism to be young men who are educated and with relatively stable socio-economic backgrounds, but with limited employment prospects.127 Childhood exposure to violence and trauma can, in some cases, create a propensity to hostility, violence and authoritarian views, which can act as “emotional precursors” to a later adoption of extremist attitudes.128

40

There are cases – particularly involving lone actor terrorists – where those who have engaged in violent extremism have personality disorders and mental health conditions.129 Generally speaking though, violent extremists are thought more likely to have “personality issues” (rather than personality disorders) that can make them difficult to engage with and which can lead to social alienation.130

41

Psychological distress brought about by particular experiences – a traumatic event, a change in employment status, inter-personal conflict – can also leave a person more receptive to extremist worldviews, or accelerate their radicalisation.131

42

Radicalisation is almost universally acknowledged as a group phenomenon in which social relations and networks play a key role in preparing people to commit extremist violence.132 A person may come into contact with extremists in a multitude of ways, such as through existing networks of friends and family, public outreach by those involved in these groups or, increasingly, online engagement.133 When someone with generalised grievances comes into contact with individuals or groups who are able to provide a wider framework through which they can understand their grievances, extremist worldviews can be reinforced.134

43

Participation in a group enables a range of processes that may facilitate the use of violence, including a solidifying of dehumanising thinking, an increased perception of crisis and belief in the use of violence as a legitimate tool.135 This is also the case for lone actor terrorists. A 2018 study analysing lone actor terrorists’ attack planning and preparation found that, for many, participation in extremist groups and access to extremist material and role models helped to break down any moral barriers they had to using violence. The wider radical environment within which they exist and draw inspiration from therefore plays an important role in their decision to undertake violence.136

44

Understanding what causes individuals to radicalise to violence is crucial for Public sector agencies, organisations, community groups and individuals working in preventing and countering violent extremism. However, radicalisation is not a linear process and factors that may contribute to one person’s radicalisation will not necessarily have the same effect for another. A person may move along the radicalisation to violence spectrum depending on the circumstances of their life at the time. All of these factors present considerable challenges for intelligence and security and law enforcement agencies in identifying and prioritising persons of concern within their finite resources.

45

Considerable effort has therefore gone into identifying indicators that could suggest someone is mobilising to violence and is actively planning a terrorist attack, such as whether a person is participating in online extremist discussion forums, has escalating anger about a grievance, is building psychological and/or technical capability (such as learning online how to make bombs) and is undertaking planning (such as conducting reconnaissance).137 These indicators are often generic and understanding their significance – for example, whether what an individual says online suggests they subscribe to an extreme right-wing ideology and are willing to act on it – requires a sophisticated knowledge of the dynamics of right-wing extremism.

64. Jayde Walker “An introduction to countering violent extremism” (2017) 5(2) Practice: The New Zealand Corrections Journal; Logan Macmair and Richard Frank “Voices against extremism: a case study of a community-based CVE counter-narrative campaign” (2017) 10 Journal for Deradicalisation; Astrid Botticher “Towards academic consensus definitions of radicalisation & extremism” (2017) 11(4) Perspectives on Terrorism; Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal Extreme-Right Violence and Terrorism: Concepts, patterns, and responses (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism Policy Brief, 2019).

65. JM Berger Extremism (MIT Press, London, 2018).

66. Astrid Botticher, footnote 64 above; Commission for Countering Extremism Challenging Hateful Extremism (Department of Security and Crime Science, United Kingdom, 2019).

67. John Horgan “From profiles to pathways and roots to routes: Perspectives from psychology on radicalization into terrorism” (2008) 618(1) The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences; Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above; United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (n.d.) “Radicalisation” and “Violent Extremism” https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/terrorism/module-2/key-issues/radicalization-violent-extremism.html.

68. Commission for Countering Extremism, footnote 66 above.

69. Commission for Countering Extremism, footnote 66 above at page 10.

70. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above.

71. Derald Sue, Christina M Capodilupo, Gina C Torina and Jennifer M Bucceri “Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice” (2007) 62(4) American Psychologist.

72. Noémie Bouhana The Moral Ecology of Extremism: A systemic Perspective (Commission for Countering Extremism, Department of Security and Crime Science, United Kingdom, 2019).

73. Commission for Countering Extremism, footnote 66 above.

74. United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate CTED Trends Alert: Member States concerned by the growing and increasingly transnational threat of extreme right-wing terrorism (April 2020) at page 2.

75. Commission for Countering Extremism, footnote 65 above.

76. Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner The Fringe Insurgency: Connectivity, Convergence and Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right (Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2017); Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner ‘The Great Replacement’: The Violent Consequences of Mainstreamed Extremism (Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2019).

77. Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2017), footnote 76 above; Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2019), footnote 76 above; Australian Muslim Advocacy Network Interim Research Report: An Introduction to Extreme Right Actors and Ideologies Targeting the Islamic Community ( August 2020).

78. Richard McNeil-Willson, Vivian Gerrand, Francesca Scrinzi and Anna Triandafyllidou Polarisation, Violent Extremism and Resilience in Europe today: An analytical framework (BRaVE – Building Resilience against Violent Extremism and Polarisation, 2019); Jonathan Githens-Mazer and Robert Lambert Islamophobia and Anti-Muslim Hate Crime: a London Case Study (European Muslim Research Centre, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, 2010); Coleen E Mills, Joshue Freilich and Steven M Chermak “Extreme Hatred: Revisiting the Hate Crime and Terrorism Relationship to Determine Whether They Are ‘Close Cousins’ or ‘Distant Relatives’” (2017) 63 Crime & Delinquency.

79. Commission for Countering Extremism, footnote 66 above.

80. Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens and Hans Brun A Neo-Nationalist Network: the English Defence League and Europe’s Counter-Jihad Movement (The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, 2013) at page 30.

81. QAnon relates to a conspiracy theory in which a “deep state” made up of political elites secretly controls the United States of America.

82. “Incels” stands for “Involuntary Celibates”. Incels are an online community of males unable to form sexual or romantic engagements. Their behaviour is informed by a misogynist ideology that men are entitled to sexual access to women and that feminists are controlling society to the detriment of men. A number of incels have committed acts of terrorism.

83. United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate, footnote 74 above.

84. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at page 3.

85. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at page 2.

86. This is referred to as shifting the “Overton window”. See Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2017), footnote 76 above at page 15.

87. It is worth noting that this refers only to cultural nationalism as it relates to the academic literature on the far right. The concept of cultural nationalism is used differently by political philosophers who argue for forms of civic or liberal nationalism. See for example: Will Kymlicka Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1995); Yael Tamir Liberal Nationalism (Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1993).

88. Peter Davies and Derek Lynch The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right (Routledge, London, 2002) at page 217.

89. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at pages 4-5.

90. Toby Archer “Breivik’s Mindset: The Counterjihad and the New Transatlantic Anti-Muslim Right” in Max Taylor, PM Currie and Donald Holbrook (eds) Extreme Right-Wing Political Violence and Terrorism (Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2013).

91. Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens and Hans Brun, footnote 80 above at page 1.

92. Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens and Hans Brun, footnote 80 above at page 28.

93. Ben Lee Overview of the Far Right (Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), Lancaster University, United Kingdom, 2019) at page 5.

94. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at pages 4-5.

95. The Identitarian movement was founded in 2003 in the South of France as Les Identitaires or (in English) Generation Identity. It is a pan-European, white nativist group that advocates an ethnically and culturally homogenous Europe.

96. Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens and Hans Brun, footnote 80 above at page 26.

97. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above.

98. Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2019), footnote 76 above.

99. Australian Muslim Advocacy Network, footnote 76 above.

100. The term “white genocide” was first popularised by the white supremacist David Lane who argued that white populations are being replaced through immigration and integration, abortion and violence against white people. It differs from the Great Replacement theory in that it is often tied explicitly to anti-Semitic conspiracy theories – suggesting that Jewish people deliberatively orchestrate population change. See Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2019), footnote 76 above.

101. The Eurabia theory was popularised in the early 2000s and claims that Western countries are slowly being brought under Islamic rule. The Oslo terrorist referenced the Eurabia concept.

102. Cultural Marxism is a theory that has been in existence since the early 20th century. It has been popularised by the far right and claims that liberal and left-wing elites are conspiring to use cultural institutions – such as universities, schools, the media and government bureaucracies – to promote ideas that set out to destroy the values that underpin Western society. The promotion of feminism, multi-culturalism and gay rights are all seen as evidence of cultural Marxism.

103. This comes from The Turner Diaries, a novel written in 1978 by neo-Nazi leader William Pierce (under the pseudonym “Andrew Macdonald”). In the novel, “The Day of the Rope” refers to the day white supremacists conducted mass lynching of all “race traitors” including politicians, journalists and women in relationships with non-white men.

104. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at page 13.

105. Jessie Daniels Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights (Rowan and Littlefield, New York, 2009).

106. Florian Hartleb Lone Wolves: The New Terrorism of Right-Wing Single Actors (Springer, Switzerland, 2020).

107. Maura Conway, Ryan Scrivens, and Logan Macnair Right-Wing Extremists’ Persistent Online Presence: History and Contemporary Trends (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2019) at page 2.

108. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at page 2; Florian Hartleb, footnote 106 above.

109. Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2017) footnote 76 above at pages 25-27.

110. Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2019), footnote 76 above at page 24; Australian Muslim Advocacy Network, footnote 76 above.

111. Maura Conway, Ryan Scrivens, Logan Macnair, footnote 107 above at pages 6-7.

112. Maura Conway, Ryan Scrivens, Logan Macnair, footnote 107 above at page 13.

113. Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner (2017), footnote 76 above at page 26.

114. Maura Conway, Ryan Scrivens, Logan Macnair, footnote 107 above at page 9.

115. Jacob Shamsian “Reddit is Allowing a Major Trump-Supporting Community to Flourish Despite Members Defending the New Zealand Mosque Shooter” Business Insider (United States of America, 22 March 2019) https://www.insider.com/reddit-thedonald-cringeanarchy-new-zealand-shooting-mosque-muslims-2019-3.

116. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at pages 13-14.

117. Maura Conway, Ryan Scrivens, Logan Macnair, footnote 107 above at page 13.

118. Tore Bjørgo and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, footnote 64 above at pages 13-14.

119. The system that generates recommended videos for the viewer based on similar content to videos selected and other viewers with similar viewing histories.

120. Kevin Munger and Joseph Phillips “A Supply and Demand Framework for YouTube Politics” (2019) Penn State Political Science. The “rabbit-hole” theory is also discussed.

121. Jarrod Gilbert and Ben Elley describe the alternative right or “alt-right” as the online white supremacist communities that grew in prominence especially after the 2016 presidential election in the United States of America. See Jarrod Gilbert and Ben Elley “Shaved heads and sonnenrads: comparing white supremacist skinheads and the alt-right in New Zealand” (2020) Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online.

122. Jarrod Gilbert and Ben Elley, footnote 121 above at page 289.

123. Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways Toward Terrorism, Terrorism and Political Violence” (2008) 20(3) Terrorism and Political Violence; Tahir Abbas Far Right and Islamist Radicalisation in an Age of Austerity: A Review of Sociological Trends and Implications for Policy (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism Policy Brief, 2020); Noémie Bouhana, footnote 72 above.

124. Kris Christmann Preventing Religious Radicalisation and Violent Extremism: A Systematic Review of the Research Evidence (Youth Justice Board/Office for Counter-Terrorism, United Kingdom, 2012); Magnus Ranstorp The Root Causes of Violent Extremism (Radicalisation Awareness Network Issue Paper, 2016).

125. Noémie Bouhana, footnote 71 above; Tahir Abbas, footnote 123 above; Jarrod Gilbert and Ben Elley, footnote 121 above.

126. Tahir Abbas, footnote 123 above.

127. Ineke van de Valk and Willem Wagenaar The Extreme Right: Entry and Exit (Racism & Extremism Monitor, Anne Frank House, Netherlands, 2010); Peter Sitzer and Wilhelm Heitmeyer “Right-wing extremist violence among adolescents in Germany” (2008) New Directions for Youth Development; Raffaello Pantucci, Clare Ellis and Lorien Chaplais Lone-Actor Terrorism: Literature Review (Royal United Services Institute Occasional Papers, 2015); Luke Munn “Alt-Right Pipeline: Individual Journeys to Extremism Online” (2019) 24(6) First Monday; Jarrod Gilbert and Ben Elley, footnote 121 above.

128. Jessica Stern “Radicalization to Extremism and Mobilization to Violence: What Have We Learned and What Can We Do about It?” (2016) 688(1) The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science; Peter Sitzer and Wilhelm Heitmeyer, footnote 127 above.

129. Jayde Walker, footnote 64 above; Matteo Vergani, Muhammad Iqbal, Ekin Ilbahar & Greg Barton “The Three Ps of Radicalization: Push, Pull and Personal. A Systematic Scoping Review of the Scientific Evidence about Radicalization Into Violent Extremism” (2018) 443(10) Studies in Conflict & Terrorism.

130. Raffaello Pantucci, Clare Ellis and Lorien Chaplais, footnote 127 above.

131. Kris Christmann, footnote 124 above; Matteo Vergani, Muhammad Iqbal, Ekin Ilbahar & Greg Barton footnote 129 above; Caitlin Clemmow, Noémie Bouhana and Paul Gill “Analysing person-exposure patterns in lone-actor terrorism: Implications for threat assessment and intelligence gathering” (2019) 19 Criminology and Public Policy; Bart Schruuran, Edwin Bakker, Paul Gill and Noémie Bouhana “Lone actor terrorist attack planning and preparation: A data-driven analysis” (2018) 63(4) Journal of Forensic Sciences.

132. Jamie Bartlett and Carl Miller “The Edge of Violence: Towards Telling the Difference Between Violent and Non-Violent Radicalization” (2012) 24(1) Terrorism and Political Violence.

133. Daniel Koehler “The Radical Online: Individual Radicalisation Processes and the Role of the Internet” (2014/15) 1 Journal for Deradicalisation; Ineke van de Valk and Willem Wagenaar, footnote 127 above.

134. John Horgan, footnote 67 above.

135. Daniel Koehler, footnote 133 above; Luke Munn, footnote 126 above.

136. Bart Schruuran, Edwin Bakker, Paul Gill and Noémie Bouhana, footnote 131 above.

137. Caitlin Clemmow, Noémie Bouhana and Paul Gill, footnote 130 above.