1

New Zealand is situated in the southwest Pacific Ocean and is geographically isolated from the rest of the world. New Zealand’s population was just over 5 million in the year 2020, with its people spread primarily over its two largest islands, the North and South Islands. Situated in the North Island, Auckland is the largest city and home to one third of the country’s population, with around 1.66 million inhabitants. Also in the North Island is New Zealand’s capital, Wellington, with a population of around 500,000 in the wider region. This is followed by Christchurch in the South Island, which has a population of around 385,500.

2.1 The Māori – Crown relationship

2

First contact between Māori and Tauiwi occurred in the 17th century. Through the late 18th century and early 19th century, European traders, missionaries and later British settlers arrived in New Zealand. The British government had no legal authority to control the activities of settlers until the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840.1

3

Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed by Māori and the British Crown in 1840. It is New Zealand’s founding document.2 With the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, New Zealand became a British Colony and it paved the way for further settlement of British citizens. Te Tiriti o Waitangi came with a duty on the part of the Crown to protect Māori rights and property. There were (and still are) different interpretations of what was agreed in the Māori and English texts of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. A significant difference of interpretation is whether Māori ceded sovereignty (as in the English text) or whether they agreed to British governance over their lands (kāwanatanga in the Māori text) but retained self-determination (tino rangatiratanga in the Māori text). The repeated failures on the part of the Crown to uphold its commitments under Te Tiriti o Waitangi have caused widespread and ongoing harms.3

4

From 1840 the pace of migration saw the Tauiwi population grow rapidly. It soon outnumber Māori. By 1874 Māori made up less than one-tenth of the population and this remained the case for a century.4

5

The colonisation of New Zealand led to Māori incurring widespread loss of land through practices in breach of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.5 This included large-scale land confiscation.6 These confiscations occurred during and after the New Zealand Land Wars, a series of battles prompted by conflict over land sales and interpretations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Through this period the Crown attempted to suppress Māori protest and self-determination, including through the use of excessive force.7 By 1930 Māori retained ownership of only six percent of land in New Zealand.8

6

The loss of land, warfare and imposition of laws, policies and practices designed to assimilate Māori9 eroded Māori social structures and led to a loss of language and traditional knowledge.10 This has had enduring impacts on Māori health, wellbeing and access to resources, which are seen today in disparities across a range of indicators.

7

Māori have sought resolution of grievances for the past 180 years have demanded recognition of their Te Tiriti o Waitangi rights and tino rangatiratanga.11 The Māori-led movement in the latter half of the 20th century, together with Waitangi Tribunal claims and subsequent negotiated settlements with the Crown,12 have contributed to the revitalisation of Māori language and culture and socio-economic development.13 The principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi form the basis of the ongoing relationship between Māori and the Crown.

2.2 New Zealand’s constitutional arrangements

8

New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy. The Sovereign (Queen Elizabeth II) is the head of state of New Zealand and is represented by the Governor-General. The Sovereign exercises certain powers and functions, acting on the advice of ministers.14 The prime minister is the principal advisor to the Governor-General.

9

The prime minister is the head of government. The executive branch of government consists of ministers and the public service. Ministers direct the executive branch of government, which makes decisions on government policies and proposes laws.15

10

Ministers are members of Parliament and are appointed by the Governor-General on the advice of the prime minister. Ministers are responsible for specific portfolios such as national security (Minister for National Security and Intelligence) or law enforcement (Minister of Police). Ministers are responsible for exercising the functions and powers provided for by their letter of warrant and as defined in legislation for their portfolios.16

11

Ministers collectively make decisions and determine government policy through the Cabinet decision-making process. Cabinet is the central government decision-making body. Issues will first be discussed at Cabinet committees before being considered by Cabinet. Cabinet committees are organised by subject areas (see Part 2, chapter 4 for a description of the Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee).17

12

As well as these collective responsibilities, ministers have individual responsibility for their portfolios. Ministers set the policy direction and priorities for their Public sector agencies but are generally not involved in day-to-day operations. They are, however, expected to answer to Parliament on matters relating to the policies and performance of the Public sector agencies within their portfolios and on public spending. Ministers are concerned not only with the short-term performance of Public sector agencies, but also with agency capability to continue to deliver government objectives in the longer term.18

13

The formal relationship between ministers and the public service is governed primarily by the Public Service Act 2020 and the Public Finance Act 1989. Chief executives serve as the main point of contact between their agencies and ministers. As set out in the Cabinet Manual 2017,19 officials are responsible for supporting ministers in carrying out their ministerial functions, for example, by developing and implementing policy and strategy within their ministers’ portfolios. They are expected to provide free and frank advice to their ministers and inform them of any significant developments within their portfolio. Officials must be politically neutral in their work.

14

New Zealand has a Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) electoral system, which was instituted in 1994. Under this system each person has two votes, one for their preferred political party and one for the preferred candiate in their electorate. Under a Mixed Member Proportional system, multi-party coalitions have been common. This requires political parties to compromise and cooperate in order to form a government.

15

The move to a Mixed Member Proportional system brought a number of changes to the functioning and performance of government in New Zealand. It reduced the dominance of the executive branch of government and expanded the scope for “more meaningful debate of the government policy”.20 This type of system requires that governments spend more time gathering support for their policies, which can slow down the decision-making process, but means public consultation is more likely to influence government policy.21 A potential consequence of this is that in the bargaining process that comes with the development and maintenance of multi-party coalitions, it may be difficult to gain support for policies that are unpopular with a significant proportion of voters.

2.3 Immigration and increasing diversity

16

Te Tiriti o Waitangi established a bicultural foundation for New Zealand, but through the Crown’s responsibiliy to govern and make laws for all New Zealanders it also established a foundation for multiculturalism.22

17

Until the late 20th century most migrants to New Zealand were of European origin.23 As recently as 1991 only eight percent of the New Zealand population reported that they belonged to an ethnic group other than Māori or European.

18

New Zealand has long had strong links with the Pacific Islands and substantial waves of migration have led to a large Pasifika population in New Zealand. In 2018 about eight percent of New Zealand’s population were Pasifika.

19

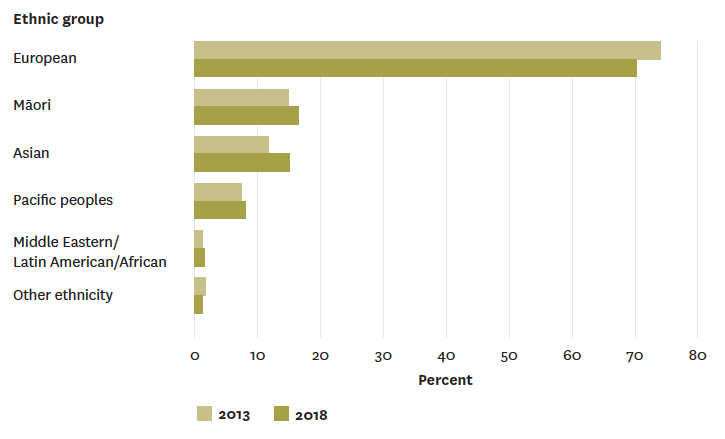

Over the last few decades, changes in immigration policy and consequential increases in immigration have seen New Zealand become a more diverse nation.24 By 2011, New Zealand was listed as the fifth most ethnically diverse country within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),25 with one in every four residents in New Zealand born overseas.26 As at the 2013 Census, New Zealand was home to 213 ethnicities and 160 languages. The change in New Zealand’s ethnic composition has happened within a generation. Auckland is now one of the most diverse cities in the world, more so than London or New York.27 New Zealand’s ethnic diversity is expected to continue increasing.28 By 2038, 34 percent of the New Zealand population will be non-European (compared with 29.8 percent as at the 2018 Census).29 The table below shows the proportions of ethnic groups as at the 2013 and 2018 Censuses.

Figure 2: Ethnic groups in New Zealand (2013 and 2018)

20

New Zealand has an aging population and it is estimated that by 2051, one in every four people will be aged 65 years and over. They will be supported by an increasingly diverse workforce.

21

New Zealand’s demographic changes have also contributed to increased religious diversity. Of those who do follow a religion, Christianity remains the single largest religion, with Catholicism now the largest Christian denomination.30 The number of New Zealanders identifying with Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Sikhism has also increased.31 Secularisation and the reduction in religious affiliation amongst European New Zealanders has also contributed to a change in New Zealand’s religious make-up.

1. Office of Treaty Settlements Ka tika ā muri, ka tika ā mua / Healing the past, building a future (2018).

2. Office of Treaty Settlements, footnote 1 above.

3. Rebecca Wirihana and Cherryl Smith “Historical Trauma, Healing and Well-Being in Māori Communities” (2014) 3(3) MAI Journal; Human Rights Commission Human Rights and the Treaty of Waitangi: Human Rights in New Zealand (2010); TK Kingi “The Treaty of Waitangi: A framework for Māori health development” (2017) 54(1) Journal of Occupational Therapy.

4. Ministry for Culture and Heritage Māori and European population numbers, 1838-1901 (29 August 2014) http://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/maori-and-european-population-numbers-1838%E2%80%931901.

5. Office of Treaty Settlements, footnote 1 above.

6. Rebecca Wirihana and Cherryl Smith, footnote 3 above.

7. Office of Treaty Settlements, footnote 1 above.

8. Office of Treaty Settlements, footnote 1 above.

9. For example, the Native Schools Act 1867, the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907.

10. Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Tessa Evans-Campbell, Ngaropi Cameron, Rihi Te Nana, Tania Mataki, Herearoha Skipper, Hinewirangi Kohu-Morgan and Kim Southey “Investigating Māori approaches to trauma informed care” (2017) 2(3) Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing.

11. Mera Penehira, Alison Green, Linda Tuhiwai Smith and Clive Aspin “Māori and indigenous views on R & R: Resistance and Resilience” (2014) 3(2) MAI Journal; Office of Treaty Settlements, footnote 1 above.

12. The Waitangi Tribunal was set up in 1975 to consider contemporary claims of breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. In 1985 its powers were extended to allow it to consider historical breaches dating back to 1840.

13. Human Rights Commission, footnote 3 above.

14. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Cabinet Manual 2017 (2017).

15. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, footnote 14 above.

16. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, footnote 14 above.

17. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, footnote 14 above.

18. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, footnote 14 above.

19. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, footnote 14 above.

20. Geoffrey Palmer and Matthew Palmer Bridled Power: New Zealand Government Under MMP (Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1997) at page 15.

21. Geoffrey Palmer and Matthew Palmer, footnote 20 above.

22. Human Rights Commission, footnote 3 above.

23. Paul Spoonley “New Diversity, old anxieties in New Zealand: the complex identity politics and engagement of a settler society” (2015) 4(38) Ethnic and Racial Studies.

24. Paul Spoonley, footnote 23 above.

25. Mai Chen Superdiversity Stocktake: Implications for Business, Government and New Zealand (Superdiversity Centre, 2015).

26. The Royal Society of New Zealand Our Futures Te Pai Tāwhiti: The 2013 Census and New Zealand’s Changing Population (2013) at page 6.

27. International Organization for Migration World Migration Report 2015 (Geneva, 2015) https://publications.iom.int/system/files/wmr2015_en.pdf.

28. Stats NZ projections, https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/national-ethnic-population-projections-2013base2038-update

29. Stats NZ, footnote 28 above.

30. Stats NZ, 2013 Census.

31. Stats NZ, footnote 30 above.