2.1 Overview

1

In the terrorist attack on 15 March 2019, the individual used semi-automatic rifles with large capacity magazines. These weapons were configured to be military style semi-automatic firearms, which the individual was not entitled to possess with his standard firearms licence. Yet he was able to legally acquire both the rifles and the large capacity magazines.

2

In this chapter we explain why this was so. For clarity, unless it is otherwise stated, we describe the relevant legislation and processes as they stood on 15 March 2019.

2.2 The evolution of the regulation of semi-automatic firearms

3

The Arms Act 1983 imposed particular limitations on the importation and possession of pistols and “restricted weapons”. “Restricted weapons” are:4

… any weapon, whether a firearm or not, declared by the Governor-General, by Order in Council made under s 4 of this Act, to be a restricted weapon.

The Arms (Restricted Weapons and Specially Dangerous Airguns) Order 1984 declared a number of weapons to be restricted, including anti-tank projectors, grenade dischargers, Molotov cocktails, machine guns, sub-machine guns, explosive mines, mortars and rocket launchers. Semi-automatic firearms were not included.

4

Further changes came about after a mass shooting in 1990 when a gunman used two semi-automatic firearms to kill 13 people in Aramoana, near Dunedin. In response to this event, the Arms Act was amended by the Arms Amendment Act 1992 to create restrictions on military style semi-automatic firearms, which were defined in a reasonably complex way.

5

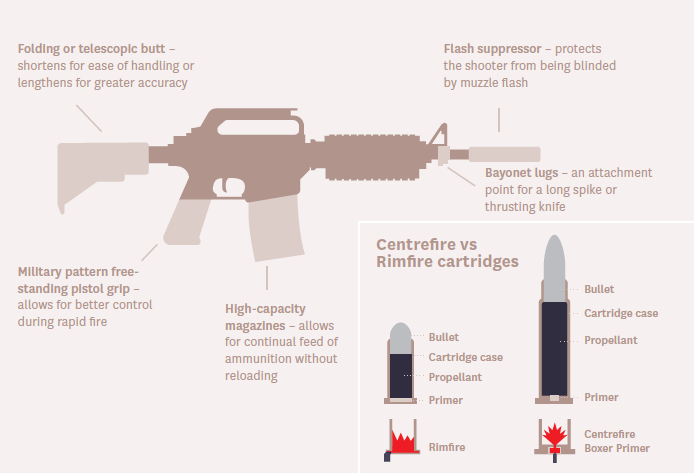

A semi-automatic firearm was a military style semi-automatic firearm if it was fitted with:

- a magazine capable of holding more than 15 .22 calibre rimfire cartridges or more than seven cartridges of any other kind; and/or

- a military pattern free-standing pistol grip; and/or

- a folding or telescopic butt; and/or

- bayonet lugs; and/or

- a flash suppressor.

Figure 14: The five components of a military style semi-automatic firearm

6

The Arms Amendment Act 1992 also introduced the following:

- A requirement for a licence endorsement (known as an E Endorsement) to possess military style semi-automatic firearms.5

- A requirement for permits to procure military style semi-automatic firearms, as was already the case for pistols and other restricted weapons.

- Import controls under a new section 18(2), requiring a permit to import military style semi-automatic firearms or parts. A permit could only be issued by the Commissioner of New Zealand Police and subject to the Commissioner being satisfied that there were “special reasons” why the firearm or parts “should be allowed into New Zealand”. The Commissioner could delegate permit approval powers to police officers of the rank of inspector or higher.

2.3 New Zealand Police practice in relation to military style semi-automatic firearms

7

A restrictive approach was taken to the application of section 18(2) of the Arms Act. New Zealand Police policy was that “special reasons” to import a military style semi-automatic firearm or parts for such a firearm would be established if:

The individual applying for the permit:

- seeks to possess the [military style semi-automatic firearm] as part of a collection, and demonstrate that it fits with and enhances an existing collection, or

- participates in an identifiable shooting discipline or sport at an incorporated sports club with rules encouraging the safe and legal use of firearms and a range certified for the shooting activity and intends to use the [military style semi-automatic firearm] in an event at that sports club, or

- wishes to use the [military style semi-automatic firearm] in a capacity equivalent to that described in section 29(2)(e) of the Arms Act 1983 (“theatrical purposes”), or

- wishes to replace an unsafe or unserviceable [military style semi-automatic firearm] or part thereof and offers a 1:1 surrender of the unsafe or unserviceable [military style semi-automatic firearm] or part of the [military style semi-automatic firearm], or

- requires the [military style semi-automatic firearm] for occupational purposes.

For dealers seeking a section 18(2) permit, special reasons were:

The dealer is importing the … [military style semi-automatic firearm] … as an agent for an individual who has a special reason for importing that item.

or

The dealer wishes to replace an unsafe or unserviceable [military style semi-automatic firearm] or part and offers a 1:1 unconditional surrender of the unsafe or unserviceable [military style semi-automatic firearm] or part.

8

A similar approach was adopted for permits to procure.

2.4 Disputes about administration

9

New Zealand Police’s administration of the legislative controls on military style semi-automatic firearms was contentious. Many in the firearms community did not see much sense in legislative restrictions that, in part, rested on the appearance of firearms rather than their functionality. The restrictive approach to the granting of permits to import military style semi-automatic firearms and associated parts was unpopular. Also unpopular was a change in New Zealand Police policy on what constituted a military pattern free-standing pistol grip.

10

Some of these issues gave rise to litigation. The restrictive policy adopted by New Zealand Police to the granting of permits under section 18(2) was upheld in Clark v Commissioner of Police where the Court rejected the argument that a dealer’s wish to have stock on hand for resale was a special reason.6 New Zealand Police, however, did not succeed in other litigation concerning:

- the interpretation of what constituted a military pattern free-standing pistol grip (where New Zealand Police’s interpretation was rejected);7 and

- whether a permit to procure was required to convert a semi-automatic firearm into a military style semi-automatic firearm (with the Court concluding that, contrary to the view of New Zealand Police, there was no need for such a permit).8

11

The Arms (Military Style Semi-automatic Firearms and Import Controls) Amendment Act 2012 re-defined military style semi-automatic weapons by removing some of the problems with the previous definition. However, this change is not material to our inquiry.

2.5 An ineffective legislative policy

12

As events turned out, the section 18(2) requirement for a permit to import parts for military style semi-automatic firearms and the restrictive approach taken by New Zealand Police were not particularly effective in limiting the importation of large capacity magazines. This is because large capacity magazines can, at least in some instances, also be used with bolt action rifles. Large capacity magazines imported for such use were not subject to import control under section 18(2). Once in New Zealand, they were not subject to any restrictions in terms of sale, meaning that a purchaser was not required to hold even a standard firearms licence. So, someone could import large capacity magazines by saying they were to be used with bolt action rifles but fit them to semi-automatic firearms (rendering those firearms military style semi-automatic weapons) but without the need for a permit.